This story was written in 2011 prior to Tex Winter's enshrinement into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. Winter passed away Wednesday at the age of 96.

It was quintessential Tex Winter, but also a metaphor for the art of basketball, as Winter believed and taught it, and which on August 12 will see him among the Class of 2011 for induction in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

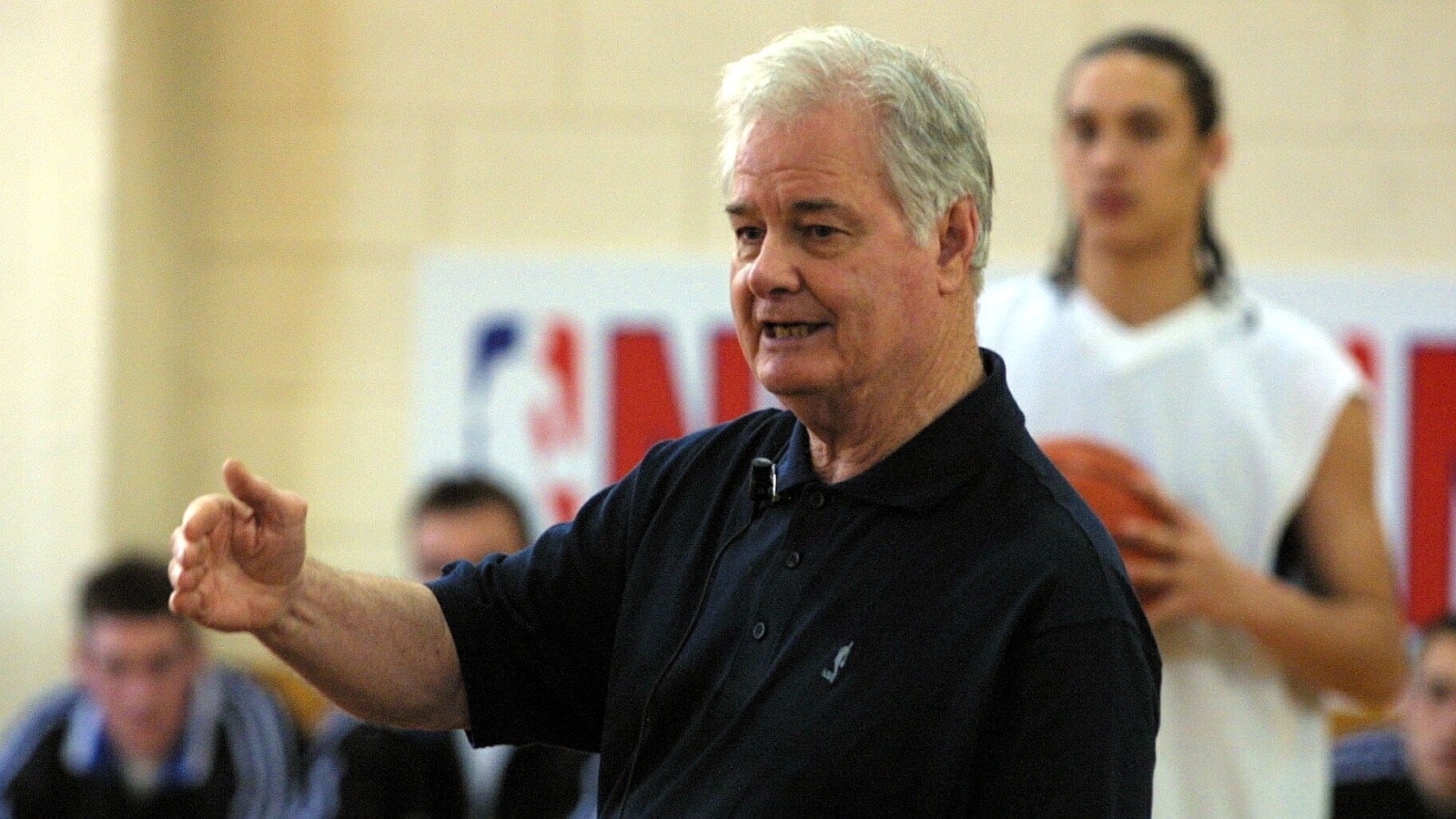

It was at one of the Bulls' private championship celebrations in that golden era, players, staff, investors and the Most Very of VIPs. Tex was with family and friends and casually making some introductions for his kids and their spouses. Everyone knew Tex from his success coaching in college and in the NBA with the Bulls and later Lakers championship teams, 10 titles as likely the most successful assistant/mentor in NBA history.

Plenty of big timers were there, like Lamar Hunt, one of the original investors in the Bulls, who also was perhaps America's most noted sportsman for helping found the American Football League, Major League Soccer, owning teams and being one of the world's richest men along the way.

Tex became famous for popularizing the triple-post, sideline triangle, or simply, triangle offense, a basketball system based on equal opportunity. It was a system based on ball movement and player movement with purpose. The reaction was to what the defense does.

"This is Lamar Hunt," Tex was saying conversationally to his daughter in law, Kim. "He's from Texas, too."

No, nothing about being from the family of oil tycoons or founding sports leagues or of being one of the founders of the Chicago Bulls. Just Lamar from Texas.

Vintage Tex, because that little anecdote says much about Morice Fredrick "Tex" Winter and the basketball philosophy that helped make the teams he worked with among the most successful in the history of American team sports.

It was, as Tex once said, based on equal opportunity, which also was something of a tenet of Tex's life. He believed if you supplied the basic elements of effort, spirit, determination, ambition and character—with, of course, some talent—you could succeed, success measured in helping your team. Not who you were, but what you did.

Tex became famous for popularizing the triple-post, sideline triangle, or simply, triangle offense, a basketball system based on equal opportunity. It was a system based on ball movement and player movement with purpose. The reaction was to what the defense does.

Sure, the Bulls with Michael Jordan had the biggest star of the game, hardly just another guy. But the system was flexible enough to adjust for individual brilliance within the team concept, which was a crucial element of the success of the 1990's Bulls and 2000's Lakers. Think of some of the guys who starred at the biggest times: John Paxson, Steve Kerr and Bobby Hansen in Chicago, just to name a few.

It was that same system which enabled Winter in a fabulous college career to defeat teams led by the transcendent stars of the day, like Wilt Chamberlain and Oscar Robertson.

Of course, you also need talent. So when Tex went to the University of Washington, he couldn't quite get by UCLA and Lew Alcindor, though no one gave them tougher games. And no one else got by them, either. When Tex went to Northwestern, his teams couldn't win consistently. But they routinely defeated top Big 10 teams.

That also was the essence of Tex as a coach.

He didn't chase awards or individual honors. The group—the team—was what mattered. So in what was pure Tex, he left one of the most successful programs in the nation, Kansas State, to his then assistant, Cotton Fitzsimmons, when Kansas State was a national power.

His teams had won eight conference titles in 15 seasons and Winter was one of the winningest coaches in college basketball, fourth most successful in college basketball when he left Kansas State. His teams finished in the top 10 nine times. He was the chairman of the NCAA rules committee. He'd written a bible on tactics, the Triple-Post Offense. He was perhaps the most in demand speaker for clinics. He was voted national coach of the year.

But Tex still went to moribund basketball programs like the University of Washington. And places where his win/loss record would badly suffer, like Northwestern. Still, it never mattered to the affable Tex because he could teach and coach and, after all, it was never about him, but the game and the players. It didn't matter who you were, but what you did. And no one was above teaching or improvement because that was the goal.

If Michael Jordan didn't pass the ball correctly, Tex explained the correct way, which he did.

"Michael said he knew he wasn't passing the ball right," Phil Jackson recalled with a laugh.

So did Craig Hodges and Billy McKinney, two of Tex's college players who went onto NBA careers despite limited physical abilities, players who were every bit as important to Tex as Jordan.

"No way I'd ever have played in the NBA without his fundamentals, the preparation, the routines he taught every day," said McKinney.

It was about teaching and helping and growing and celebrating the game, no matter who you were. That, really, is what makes you a Hall of Famer.

It was a tough life for Tex growing up in dusty West Texas during the years of the Depression and the Dust Bowl. His father died of an infection when Tex was 10 and Tex had to work while in elementary school to help support the family. Sometimes you never can forget, and Tex admits he always kept the little shampoo and lotion bottles from the team hotels. One of his jobs as a kid was to collect boxes for a local baker in exchange for day old bread for the family. For years, Tex always kept boxes and would get the trainers to give him the Nike sneaker boxes. Hey, you never know.

It helped cement the reputation of being the absent minded professor. But until you've been there, you cannot know the hardship. "I lived through when we hardly had enough," Tex once told me. "I don't forget."

But life finally changed a bit for the better when he was in high school. His older sister had married and moved to California. He and his twin sister and mom joined her while his football star brother stayed behind to finish school in Texas, though not like it was the gold rush. Tex still worked to help support the family, boxing produce at a local market and paid in day old vegetables and fruits to help feed the family.

Though there was no expense spared for the game.

Tex while coaching was an evangelist of the game. He'd go anywhere to teach it, to conduct clinics. Iceland, New Zealand, the Philippines, and if there wasn't a budget, he'd pay. Though this still was Tex the child of the Depression, who always wondered why everyone ate out on the road when there were these fabulous—in his view—free press room meals of meat and mashed potatoes.

When the Lakers or Bulls would send him to scout, he'd get the senior citizen airfare rate. One time he was going to do some advanced scouting for the Bulls while they were in New York. He was to see the Nets in New Jersey. He insisted on going to the Port Authority terminal to take a bus even though the team would pay for taxi or limousine. A waste of money, Tex said, and took the bus.

But it always was a first class ride during the games with his triangle offense, perhaps the ultimate in pure basketball. There were no play calls or numbering systems. Players reacted to the defense, passed the ball and moved until the best shot presented itself.

After high school, Tex attended junior college in Los Angeles, where he became a renowned pole vaulter and earned a scholarship to Oregon State.

Tex adapted the triangle concept playing for Sam Barry at the University of Southern California with teammates Bill Sharman and Alex Hannum, the latter who went on to use variations of the triangle in successful NBA and Hall of Fame careers. Tex went to USC when he got out of the Navy after World War II as a fighter pilot.

Tex's concepts also came from years of study from being a ball boy for Loyola University while Tex was in high school. As ball boy at Loyola, Tex would work with Phil Woolpert, who went on to coach Bill Russell at the University of San Francisco and Pete Newell, who won the national championship at the University of California with his motion offense. Newell later would hire Tex to coach the San Diego/Houston Rockets. Tex also played summer league basketball in L.A. against Jackie Robinson.

Tex became a starting guard for his Navy team during the war on the recommendation of his commanding officer, Chuck Taylor, the developer of the famous Converse sneaker, and Tex in a game at Chicago Stadium against Northwestern went against famed future quarterback Otto Graham. Then at the Chicago relays, Tex finished second to the world record setter in the vault.

Tex would publish his famous Triple-Post Offense book in 1962, and typical of the teacher that Tex was, it was the student who mattered most.

Tex left USC to become the nation's youngest head coach at Marquette, though the essence of Tex was leaving the power schools like Kansas State to take the head coaching job in the Big 10 at Northwestern.

While Tex was just 44-87 at Northwestern, they beat Magic Johnson's Michigan State team and the high flying Michigan team with Rickey Green and Phil Hubbard. Like Tex used to joke, "There are a lot of teams we can beat. They just aren't on our schedule."

While at Washington, Tex routinely coached against the UCLA dynasty with Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Sidney Wicks, Curtis Rowe and Lynn Shackleford. In one 10-day stretch playing UCLA twice, Tex's team led both times at halftime and barely fell late even with top players hurt. Said John Wooden: "Even if all five Washington players should break their legs, there'd be ample reason to fear Winter."

Tex got his nickname when the family moved to California. He was small early in high school, maybe 5-8 and 125 as a sophomore, and though not a star, he was fast and was a leader. He could have been a track star, but was found to have an enlarged heart and prevented from running. So he took up pole vaulting and was a natural. He would eventually compete frequently against a University of Illinois vaulter named Bob Richards, who placed third in the 1948 Olympics with a vault of 13-9. The winner was at 14-1. Tex had been injured in the trials, but already had vaulted 14-4. Richards would go on to star in the 1952 Olympics and be immortalized on the Wheaties box. Tex made the Olympic team when the Olympics were cancelled during World War II.

Tex met his wife, Nancy, at Oregon State. Both joined the Navy and Tex went into aviation for fighter pilot training. After the war, Tex was selected to be a test pilot for experimental jet craft, or as he later put it "a guinea pig." Four of the eight pilots died in training. Tex was Top Gun before we ever heard the name.

Tex eventually became a flight instructor back in Texas, where he met Barry, who then recruited Tex to USC.

Tex was a sponge in studying and learning the game, every day of his working basketball life like the first day. Jackson said Tex still would chart every play during games and there'd be times he'd run out of paper and be writing on the leg of trainer Chip Schaefer. Tex was always detail oriented with a lesson plan, the ultimate teacher.

One time with the Bulls during the Finals against the Jazz, Tex got called for a technical foul. He was devastated to be costing his team a point. He'd been telling the official they were missing illegal back picks being set by John Stockton. The official said Tex didn't know he was talking about. "Check page 44, section 33," Tex said.

Technical!

Tex wasn't one to defer to anyone when it came to the game. Tex would frequently jab Jackson when he wasn't calling timeouts, "You're being outcoached! Get going."

And Tex was the one when the Bulls were falling well behind in Game 6 of the 1992 Finals who told Jackson, "Get Jordan out. He's hurting us."

If you wanted honesty, you asked Tex. Or listened. Jackson did remove Jordan and the Bulls went on to overcome a 15-point fourth quarter deficit and win their second title.

"He seemed to always come up with an idea that would solve a problem and help us to a championship," said Jackson.

After graduating from USC, Tex became an assistant to Jack Gardner at Kansas State, and at 28 became the nation's youngest head coach at Marquette. After two seasons at Marquette, Gardner left Kansas State and Tex returned as head coach.

It was a brilliant, memorable run with not the most highly recruited players, but a much copied system of play that would defeat the giants. There was the memorable win over Kansas and Wilt at the end of the 1957-58 season that sent Wilt to the pros and Kansas State to the NCAA's as back then only the conference champion went. Then in the tournament, Kansas State beat Oscar Robertson and the No. 1 ranked Cincinnati. Reports at the time called it one of the biggest games of the era.

"Tex had an offense that was unique," said Jackson. "And then he was the guy always in early watching game film, talking always with players about ways to improve their game within the offense. His dedication was truly inspirational and instrumental to everything we've been able to accomplish."

Tex would publish his famous Triple-Post Offense book in 1962, and typical of the teacher that Tex was, it was the student who mattered most. I once asked Tex to help me with the offense. He brought me the book to read. I looked inside and realized it was the copy he'd inscribed personally to his mother. I told Tex I couldn't borrow it, that it was too valuable. Tex said it was more important I learn what I needed.

It was that influence that inspired a generation of coaches, from the likes of Bill Guthridge and Gene Keady at Kansas State, to Dale Brown, a high school coach Tex befriended, to Jackson, who adopted the triangle for use with the Bulls and Lakers to become the most successful coach in NBA history.

Brown was an unknown North Dakota high school coach. Tex was a legend at Kansas State. Brown was enthralled with the Triple-Post Offense book and called Tex. He said he wanted to use its principles for his teams. So Tex invited Brown to Kansas. Kansas State was ranked No. 1 in the nation at the time. Brown came and Tex ended up having Brown stay at his home with him as they talked about the game and the offense long into the night.

"Basketball and teaching was his calling," said Jackson. "Like a missionary."

It's why Tex left the larger stage of Kansas State to take on projects like the NBA's Rockets just as they moved to Houston and had to play a "home" schedule with games as far away as San Antonio, the University of Washington to compete against the giants at UCLA, Northwestern and then Long Beach State.

"The things we did every day, the fundamentals, the detail, the mental and physical preparation, some guys would laugh," recalled McKinney, now an executive with the Milwaukee Bucks. "But every year we'd beat top ranked teams. That was our signature. We just didn't have the talent to do it consistently."

Another protégé was Jerry Krause, a scout who reveled in Winter's detailed practices at Kansas State. When Krause was named Bulls general manager in 1985, his first hire was Winter, who served first as an advisor until Jackson was hired and embraced Winter's systems, philosophy and beliefs.

"He's the best teacher of the game I've ever been around," said Krause, who scouted and was an NBA executive for more than 30 years. "He has a great feel for people. He teaches big men better than anyone I've ever seen. If he were an economist or scientist, he'd have the Nobel Prize. Just a special guy. He'd turn donkeys into thoroughbreds."

Winter then took a seat by Jackson's side until a stroke at a Kansas State reunion in 2009 limited Tex from fulltime Lakers' involvement.

"Tex had an offense that was unique," said Jackson. "And then he was the guy always in early watching game film, talking always with players about ways to improve their game within the offense. His dedication was truly inspirational and instrumental to everything we've been able to accomplish."