MJ is back with the Bulls.

Sometimes he thinks about his high flying days, the dunk contests, the triple doubles, the time he embarrassed Dr. J, the full court flights of fancy and fancy flights, taking that rebound and gliding full court, a sprinter's body with a player's intentions.

MJ leaned back, the warmth of the bright Los Angeles sun enhancing the reverie. He was traveling with the Bulls last week on the Western Conference road trip, offering a little advice as an inspirational figure and taking some time to visit some of his famous Hollywood friends from back in the old days.

"Doing some ambassador work for the Bulls," Mickey Johnson was saying. "They've allowed me to talk to some of players, offer some advice. I'm very appreciative of being able to be in this position."

No, he isn't that MJ; in fact, he was known as Rubber Band Man in a 12-year NBA career that was perhaps the most unlikely in a world of unlikely stories. "Actually my nickname in high school was BC, which meant Bony Child," Johnson said with a laugh. "I was 180 pounds my first year in the pros, 6-10 and 180."

And 40 years before his time.

Magic come into the league and I was able to guard him; I was fast enough. Magic couldn't guard me on the post up.

Mickey Johnson

Wallace "Mickey" Johnson was probably the first point forward in NBA history, though no one knew it then or quite knew what to do with him. And not only because he couldn't make his Lindblom High School team and paid his way through west suburban Aurora College trying to achieve his goal of getting into a Sears training program. But could he run, a world class sprinter in high school with a guard's ability to handle the ball and a big man's size to finish. Mickey was unique, a round peg in a very square era of NBA basketball.

You know, 6-10, you get by the basket. Little guy, you dribble.

"The game I played was what they are doing now, Scottie Pippen, KD," Johnson said. "I was just as good as the guards bringing the ball up. I was fast and could run all day, not like a typical big man at the time. That's 1975, 1976. The problem was the coaches didn't know what to do with me. I remember Norm (Van Lier) told me if I don't pass him the ball he wasn't passing it back to me. I told Norm, 'I get the ball first with the rebound. I really don't need you to bring it up and pass to me.'

"It was totally different for a big man back then," added Johnson. "Players now are slimmer and can handle the ball, things I was doing in the 70s with big man moves inside. Magic come into the league and I was able to guard him; I was fast enough. Magic couldn't guard me on the post up. But the coaches didn't understand."

Still, Johnson averaged more than 15 points for five consecutive seasons, culminating with a career high 19.1 in 1979-80 with Indiana. That was even after being benched when the team traded for an aging but popular George McGinnis. Johnson was among the league leaders in scoring at the time of his demotion and still ended the season as the team's scoring leader.

Though he never could quite escape the stigma of being from the University of Nowhere, the NBA still something of a caste system. C'mon seriously, Aurora College?

"My biggest problem probably was first time something went wrong it always was, 'Mickey didn't have the experience because he went to a small college,'" Johnson recalled. "When we lost to (eventual champion) Portland in '77, I had a bad game first game (eight for 25 for 19 points and 10 rebounds). Maurice Lucas took advantage of me, but I still led the team in scoring for the series (27.3 per game along with 13 rebounds). I was always an outsider. But I never played for the money, but that love and respect for the game. Nobody can ever say Mickey held out for this or that, cried about salary. I just played. Seeing the world from the bottom up and not top down. A lot can happen in your career, but you try not to take it personal. Do what the coach wants, be there for your teammates. From humble beginnings you can reach greatness, but that greatness can also bring you back down if you let it. It's one of the reasons the Bulls asked me here."

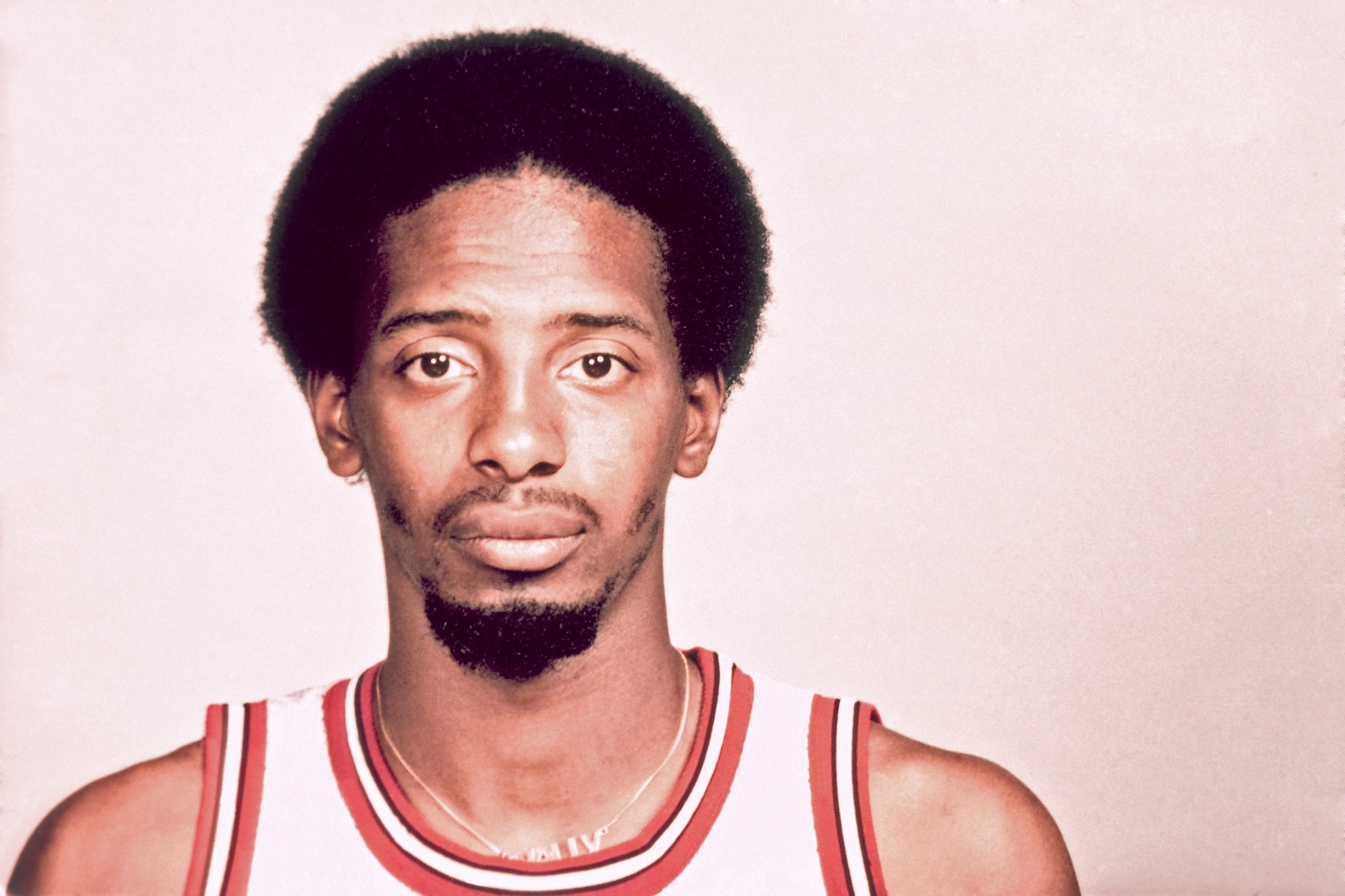

1978: Mickey Johnson poses for a portrait.

Johnson accompanied the Bulls on their road trip at the invitation of coach Jim Boylen, who is encouraging players to understand and appreciate their ancestors. Mickey took the opportunity to spend some time with his old buddy from the Temptations, Louis Price.

He's one of those veterans who perhaps may help the Bulls get ready to find their cloud nine. Cliff Levingston, Horace Grant, Scottie Pippen, Toni Kukoc and Bob Love are some of the former Bulls bring in various ambassador and supporting roles for the team.

Boylen receives some kidding about his fondness for talking about pride in the organization, Bulls on their chest. But players like Mickey Johnson can help deliver an appreciation for the game and perhaps some perspective on where they've been and where they are going.

Especially considering Johnson's excellence in the NBA over a decade despite the most unlikely roots and a vision to give back beyond basketball.

Mickey once ran for alderman in his home 24th ward North Lawndale neighborhood. He was a coach at Malcolm X College and has run a successful business, Concerned Pest Control, and worked for the county sheriff's department for almost 20 years. He's been a citizen advocate, a businessman and motivational speaker.

He also was believed to be the only player ever to block Dr. J's dunk and one of the few to have intercepted Kareem's sky hook

"Bill Willoughby and myself are the only two to have caught the sky hook out of the air," Johnson insists. "Did that twice and Willoughby once.

"I had some hops," Mickey says with a bit of a smirk.

"You didn't dunk much back then unless you had a clear path," he said. "They'd knock you down. If you dunked you had to get out of there real quick."

Johnson was quick. He also was one of the dunkers when CBS in 1977 after that first NBA dunk contest following the merger with the ABA had a season long dunk contest at halftime of its game of the week. It was won by Darnell Hillman over Kareem, though Johnson had an array of 360s, reverse and off the backboard dunks winning in earlier rounds.

"My biggest asset, though, was my ball handling ability and speed," he says. "I was faster than most guards. I used to run the 100 as a college sprinter in maybe 10 seconds, a little less. Used to lose in the finals."

It's a heck of a sprint from a simple life on the tough West Side for a kid from a large middle class family, his dad a postal worker, who couldn't make his high school team.

"Made it my sophomore year only, but didn't play," Johnson recalls. "Coach basically wanted me to be the water boy. Played one game my sophomore year. I kept trying out and didn't make it. Played YMCA basketball, summer ball. I guess the coach just felt I wasn't talented enough. I was disappointed, but I wasn't mad. No hard feelings. He did his job. I did the best I could."

It's an equanimity that masks an athlete's heart.

They weren't scouting Aurora College then, but my stats lured some professionals...I still didn't think I'd make it. I just wanted to make the best of an opportunity if it came.

Mickey Johnson

Mickey played around the neighborhood like just about everyone else, even on a team for the high school coach who always cut him.

A neighborhood man organized a team and they'd venture out to play small college teams, like Judson, George Williams, Rockford, Aurora. Mickey could score and run down a deer, and he was now close to 6-8. Aurora coach Roald Berg said he'd help him get his degree.

"You wanted to get a college education, a job, a family and all that, typical American life," Johnson said.

"The other coaches just looked at me as a ballplayer. Coach said if I come there he would help me in trying to get a degree," Mickey said. "That's why I went there. No scholarship, NAIA Division 3. Class enrollment of maybe 600 students on and off campus. I stayed on campus to work, construction and janitorial work; my mother gave me about $300 to help. I majored in business administration and economics and got my degree. My goal was to get a job at Sears to be a buyer. I put in my application after graduation."

"What happened was (Bulls) Coach (Dick) Motta had his basketball camp there and I worked for him in the summer," said Johnson. "They weren't scouting Aurora College then, but my stats lured some professionals. I averaged 26 and 20 for four years. I wasn't getting any big publicity from the major newspapers. A couple of scouts came through going to see Billy Harris (Chicago playground legend from Dunbar High School at Northern Illinois). So they stopped to see me. One had dropped a note on the floor. My coach found. It said I couldn't make the pros.

"I didn't really feel I could make it until my senior year," Johnson agreed. "There was a little more publicity and I began to feel I'd have an opportunity. I still didn't think I'd make it. I just wanted to make the best of an opportunity if it came."

Mickey Johnson looks to move against Larry Bird.

It's something of a lesson plan Boylen also delivers these days. Take advantage of your chance. Look at Mickey.

Johnson was a surprise fourth round selection of the Portland Trailblazers in the 1974 draft, though they would cut all their draft picks other than Bill Walton. Motta remembered the kid who helped him out, so he offered a conditional third round pick for Johnson, meaning he'd have to make the team. It was more charity since Motta didn't want to keep Johnson; didn't believe he was an NBA player. Expected to keep the pick.

"He said I was a nice young man and he wanted me to have the experience of being in a pro camp," Johnson said. "He said he only had me there for a taste for the money. I made about $500 a week. It was great money. He rescued me. But I never took the Sears thing off the table. I still wanted to be a buyer, and I was working in the post office to make some money."

Johnson was last man among rookies that included highly regarded Cliff Pondexter, Leon Benbow and Bobby Wilson. Motta wanted Johnson out, but he wanted Mickey to make that decision.

"He had me run suicides, three under 30 seconds," Mickey recalled. "Then he made me run three against each individual rookie; that's nine and the three for 12. Then he made me run three more by myself in under 30 seconds. But I still did it. I wouldn't give him the excuse to cut me. I passed out. It was raining that day. Motta to this day doesn't know I passed out. I'm laying on the ground outside passed out in a puddle. He wanted me to quit, but I wasn't going to give him a reason. It's what you learn, things I can pass on."

Then good fortune came his way. Bob Love held out, Pondexter was hurt and another draft pick, Maurice Lucas, went to the ABA. Then early in the season, Motta as he was wont to do went berserk when Bill Hewitt missed a layup and the Bulls lost to the Bucks. Johnson got his job.

Mickey rarely played as a rookie as the Bulls lost in the conference finals to the Warriors. But Chet Walker retired after the season, Love held out again, Pondexter was hurt again, and Johnson hung on again. Johnson got a start and never gave up the job with the Bulls.

Mickey Johnson drives on Robert Parish

He averaged at least 15 points the next four seasons with the Bulls with that unique style of play, the speed and elusiveness that is custom now and was a mystery then. He would average 14.1 points and 7.2 rebounds over those 12 seasons. Not bad for basically never having made a high school team.

Johnson went to Indiana in 1979 as one of the first free agents from the Oscar Robertson agreement that included the ABA merger. He had his best season until Indiana went sentimental. Then he bounced around, though still a unique player who played all five positions at times, Draymond Green with a shot. He posted triple doubles, played point forward for Don Nelson in Milwaukee, ran for Johnny Bach in Golden State. He finished up with the Nets in 1986 as MJ was making his mark with the Bulls.

Johnson, 66, was working around Chicago when Tina Berto with the Bulls asked if he's help with a speaking engagement. "They wanted someone else," Johnson says. "They didn't know who I was. But I told them some of the things they didn't hear from NBA players. They liked it."

So have the Bulls and Jim Boylen. Mickey Johnson showed himself and the basketball world and it's a model for these Bulls. If you never give up, you never know how far it will take you. MJ's back where he belongs.