George Gervin won four scoring titles and was a five-time All-NBA First Team selection.

> Archive 75: George Gervin | 75 Stories: George Gervin

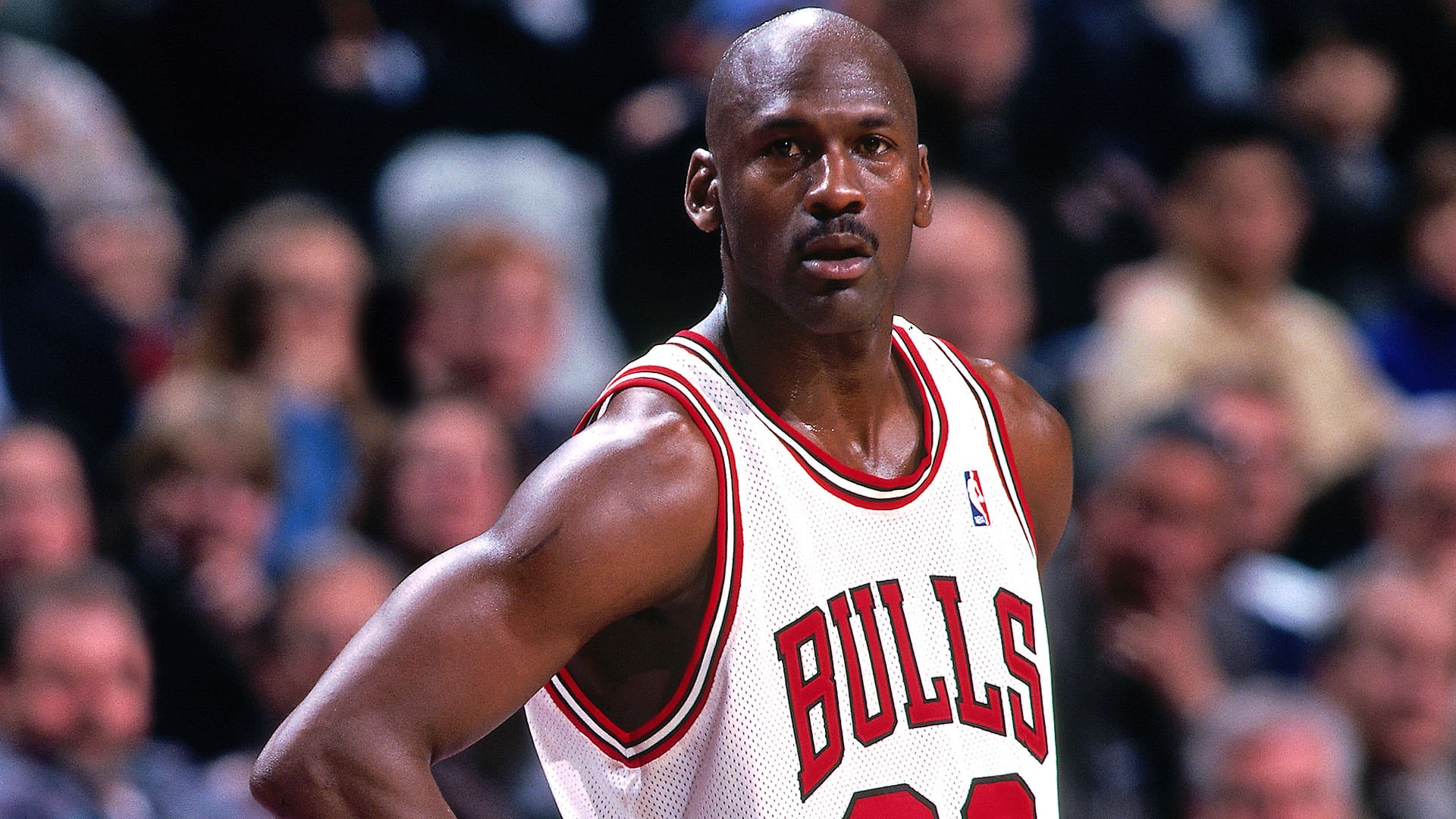

George Gervin’s playing record speaks volumes. Only Wilt Chamberlain and Michael Jordan have won more league scoring championships than Gervin’s four, and he was the first guard ever to win three titles in a row. His career scoring average of 26.2 points per game is among the game’s best as is his combined NBA/ABA total of 26,595 points.

During his career, Gervin recorded a remarkable streak of scoring double figures in 407 consecutive games. He played in 12 straight All-Star Games, including nine in the NBA and he averaged at least 21 points in each of those dozen years. In his nine NBA seasons with San Antonio, the Spurs won five division titles. He won an All-Star Game MVP Award and twice placed second in voting for the regular-season MVP Award.

But these numbers only begin to tell the story of Gervin’s phenomenal pro career, which stretched from the early 1970s through the mid-1980s. To fully appreciate the greatness of “the Iceman” one had to see him rise up for a silky-smooth jump shot from 25 feet, twirl a heavenly finger roll while soaring through the lane, execute a graceful reverse layup with either hand or explode for a sneaky power dunk between a pair of 7-foot defenders.

Whether he was battling a triple-team or changing directions in midair, Gervin made seemingly impossible shots look as easy as free throws. Despite his penchant for taking challenging shots, Gervin made more than half of his NBA field-goal attempts. Ironically, his effortless style of play prevented him from attaining the celebrity status of more dramatic players such as Julius Erving, Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan.

“He’s the one player I would pay to see,” Jerry West told the Los Angeles Times in 1982 after Gervin won his fourth scoring title. Longtime NBA coach Dick Motta told the Sacramento Bee that same year, “You don’t stop George Gervin. You just hope that his arm gets tired after 40 shots. I believe the guy can score when he wants to. I wonder if he gets bored out there.”

George Gervin took the finger roll to another level, winning four scoring titles and being named to the All-Star team nine times in his 10 year NBA career.

Gervin took an unlikely road to the NBA. One of six children, he was raised in poverty in Detroit. When Gervin was just a toddler his father left the family in the hands of George’s mother, who took any job she could find. “I’ll never know how she did it, but she had to be an awfully strong lady,” Gervin said. “Looking back, I don’t know how we made it. Somehow, she always made sure that we were never hungry.”

George started playing basketball at a cousin’s house with a neighborhood kid named Ralph Simpson, who went on to star at Michigan State and with the ABA’s Denver Nuggets. “I was just running the streets like any other kid, but the difference was that I was in love with basketball,” Gervin remembered. “You live in a city like that and you’re living in a state of war. You don’t realize it then. You just take it day by day.”

As a 5-foot-8 sophomore, Gervin tried out for the basketball team at Martin Luther King High School. He could move well but needed some work on his shot. “Cut him,” the head coach told his assistant, Willie Meriweather, who also oversaw the junior varsity team. But Meriweather liked Gervin, so he persuaded the varsity coach to allow him to carry an extra player on the junior varsity squad. Meriweather and Gervin grew close. “He was my teacher,” Gervin told the Sacramento Bee. “He was basically like a father to me.”

Meanwhile, the shy but likable Gervin had also befriended the school’s janitor, a man he knew only as Mr. Winters. Every night Mr. Winters let Gervin shoot hoops in the gym on the condition that he sweep up before he left. “It gave me solitude. I was alone in there for hours. There was nothing but me and my imagination,” Gervin said. “I had nothing else to do. In a way, I was really a fortunate kid. I never cared about crime, mischief, dope, or any of that other ghetto stuff. The only thing I cared about was basketball.”

Although he improved by leaps and bounds on the court, Gervin struggled in the classroom. Poor grades forced him to miss half the games during his junior year. Meriweather urged him to catch up in summer school. Having sprouted to 6-foot-4, Gervin finally got it all together for his senior year. He averaged 31 points and 20 rebounds to lead his school to the state quarterfinals.

Then a momentary loss of control derailed a career that was just getting back on track. While competing in a Division II tournament in Evansville, Indiana, Gervin slugged a Roanoke College player named Jay Piccola. Gervin had never before hit a player in anger during a game.

The results were disastrous. Eastern Michigan coach Jim Dutcher resigned. Gervin was suspended for the following season and eventually was kicked off the team. The official reason for the dismissal was Gervin’s inadequate performance on an NCAA eligibility exam; Gervin believed otherwise. Invitations to try out for the Olympic and Pan-American teams were withdrawn.

With nowhere else to turn, Gervin joined the Eastern Basketball Association, then one of the more successful minor-leagues. He was earning $500 per month and averaging about 40 points for the Pontiac (Michigan) Chaparrals when he got a break. In the crowd one night was Johnny Kerr, a scout with the Virginia Squires of the talent-hungry ABA. Gervin erupted for 50 points. After the game, Gervin had a new job that paid $40,000 a year.

The 1972-73 Squires already featured Erving, a second-year forward out of the University of Massachusetts. Gervin was as smooth as “Dr. J” was flashy. Gervin joined Virginia at midseason and averaged 14.1 points the rest of the way while Erving (31.9 ppg) won the scoring title.

Squires guard Fatty Taylor took a look at Gervin one day and called him “Iceberg Slim,” the nom de guerre of a slender pimp who had just written a best-selling autobiography about his former life on the streets of Chicago. “That’s the image I lived with my whole life,” Gervin said. “Big cars, a big hat. Live fast, die young. People in Detroit, the ones I hung out with, that’s the way they lived.” The name eventually evolved into “the Iceman,” which referred more to Gervin’s on-court composure than to his resemblance to a street hustler.

During the 1973-74 season, the same day Gervin played in his first ABA All-Star Game, his contract was sold to the San Antonio Spurs, who had just moved from Dallas and were known as the Chaparrals. Seemingly as par for the course for matters involving player movement during this era between the NBA and ABA or within the ABA, there was a contractual dispute. The teams and the ABA League Office all had different interpretations of the deal. The 21-year-old Gervin went into hiding during the week’s time it took to resolve the deal granting his services to the Spurs.

'The Iceman' shows every move imaginable to light up the Bucks for 50 points on March 6, 1982.

Once he began to play, Gervin was in his element. He scored 23.4 points per game for the season to rank fourth in the league. He remained in the top 10 in scoring and made the All-Star team in each of the next two years. For 48 minutes, Gervin teamed with childhood buddy Ralph Simpson on the West squad in the 1975 ABA All-Star Game.

When the Spurs joined the NBA in 1976, many observers expected Gervin to be good but not great. To their surprise, Gervin won four scoring titles in five years, earned five selections to the All-NBA First Team and appeared in nine straight NBA All-Star Games.

In 1977-78, only their second year in the league, the Spurs paced the Central Division with a 52-30 record, third best in the league. Coach Doug Moe, who had taken over when the franchise switched leagues, managed to build a winning team despite having only three double-digit scorers. Gervin won his first scoring title with 27.2 ppg; behind him were forward Larry Kenon (20.6 ppg) and hulking center Billy Paultz (15.8 ppg). A cast of little-known players filled out Moe’s roster.

That year, Gervin needed to score at least 58 points in the season finale on April 9 in order to edge out the Denver Nuggets’ David Thompson for the scoring championship. Thompson had pumped in an impressive 73 points earlier in the day to put the pressure on. When Gervin opened the Spurs’ game against the New Orleans Jazz with six straight missed shots, he asked his teammates to abandon the chase; they ignored his request and kept feeding him the ball.

Finally heating up, he scored a record 33 points in the second quarter — re-establishing an NBA record set earlier that evening when Thompson scored 32 in the first quarter — en route to a 63-point evening. Gervin squeaked by Thompson for the scoring title, 27.22 points per game to 27.15, and he finished runner-up to the Portland Trail Blazers’ Bill Walton in NBA MVP balloting.

George Gervin wowed fans throughout his career with the move he became synonymous with: the finger roll.

The following season, Gervin (29.6 ppg) repeated as scoring champion and again finished runner-up in the MVP voting, this time behind Moses Malone of the Houston Rockets. In that 1978-79 season, Gervin came closest to playing in the NBA Finals. After besting the Philadelphia 76ers in a seven-game conference semifinal series, the Spurs blew a 3-1 lead over the Washington Bullets in the Eastern Conference Finals.

With Gervin aboard, San Antonio, after moving to the Western Conference, again reached the conference finals in 1982 and 1983, losing both times to the Los Angeles Lakers. By that time Gervin had been joined by talented forwards Gene Banks and Mike Mitchell and daunting center Artis Gilmore, himself a former ABA superstar. And Johnny Moore was developing into an effective playmaker to complement Gervin’s scoring prowess.

The Spurs had gone through several coaches since Doug Moe left for Denver in 1980, including Bob Bass (for two short stints), Stan Albeck and Morris McHone. The arrival of new head coach Cotton Fitzsimmons in 1984-85 spelled the end of Gervin’s 12-year career with the Spurs’ organization. The two never hit it off. Fitzsimmons apparently believed that Gervin was weak on defense and that he feared taking the last shot in close games. After reaching the 25,000-point mark for his career, Gervin was traded to the Chicago Bulls in the ensuing offseason for forward David Greenwood. Gervin left the Spurs with 23,602 points and more than 60 team records.

Similarly as he entered the ABA playing alongside a second-year, future great named Julius Erving in 1985-86, his last season in the NBA, he joined another second-year future great player. This one was named Michael Jordan. Jordan, however, was limited to 18 games because of a broken foot, and Gervin played a valuable role for Bulls coach Albeck. The 33-year-old Gervin played in every game and averaged 16.2 points, second on the team to Orlando Woolridge. He retired from the NBA after that season with 20,708 total NBA points and a combined ABA/NBA total of 26,595.

The following year, Gervin played in Italy for Banco Roma and scored 26.1 points per game. As a newly retired player, Gervin had trouble making the transition. He developed a substance abuse habit that required three trips to rehabilitation clinics to break, the last visit coming in 1989 at a Houston facility run by former Spurs teammate John Lucas.

Spurs icon George Gervin reflects on his career, the San Antonio faithful and more.

Gervin then became addicted to a much more innocuous activity: golf. A 7-handicapper, Gervin founded an annual golf tournament in San Antonio. In 1989-90 he attempted a brief comeback with the Quad City Thunder of the CBA, appearing in 14 games and averaging 20.3 points.

Gervin worked as a community relations representative for the Spurs until 1992, when head coach Lucas made him an assistant. After two seasons on the bench, he returned to his position in the community relations department in 1994.

Gervin’s No. 44 jersey has been retired by the Spurs. And in 1996, Gervin enjoyed a banner year as he was named to the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team and was also inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Since 2017, Gervin has served as coach of the Ghost Ballers in the Big3 league.