Back in the day - before the factories were shut down, single-class basketball was assassinated and gaming and social media took their grip on the interests of young boys – the basketball games at Central High School's fieldhouse galvanized Muncie.

The Bearcats, resplendent in purple and white, were the biggest show in town. They were the greatest on Earth as far as most of the local citizens were concerned, a vortex that inhaled a community, instilled pride and knit generations together.

Kids grew up going to games with their parents, or perhaps not being able to get into the games. Either way, dreams were hatched. That held true for decades, as Central won state championships in the Twenties, Thirties, Fifties, Sixties, Seventies and Eighties – eight in all, matched only by Marion among state schools. Central fans, though, will quickly remind you all of their championships came in the single-class state tournament while Marion needed two in the multi-class tournament to pull even.

Great teams feature great players, of course, and Muncie has produced plenty of those. Four of them were voted Mr. Basketball and many more than that earned all-state honors. Some have made it to the NBA. Bonzi Wells, Central High class of 1994, lasted the longest, playing 10 seasons.

The real story of Muncie's basketball tradition - which will be honored at Bankers Life Fieldhouse on Friday when the Pacers meet Miami – has more to do with the fans than the players, though.

Muncie Fieldhouse, built in 1928, held 7,635 people, although nearly 9,000 would cram themselves in by sitting in aisles and stairwells. It was merely the sixth-largest in the state, but also the sixth-largest in the world. The city needed every one of those seats and more, because back in the glory days you had to buy season tickets to go to a game. Good luck with that, because they usually were passed on in wills. In later years you might be able to get in with a single-game ticket, but you probably had to show up before the junior varsity game to get a decent seat.

Get the people who attended those games and played in that fieldhouse talking about it, and the passion is evident even over the telephone.

"It was the greatest thing in the world," Marty Echelbarger says. "It was an unbelievable thing. It was just a dream."

Echelbarger, a member of Central's 1963 state championship team, is one of 13 Central High graduates to be inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame. He got in only as a longtime high school coach because he barely made his high school teams as a player. But he as much as anyone represents what makes Muncie's basketball history special.

Echelbarger was a nine-year-old kid in 1954 when Muncie Central lost that historic game to Milan in the championship game at Butler's fieldhouse. Bobby Plump's game-winning jumper became a legendary moment in tournament history and inspired a class sports movie, "Hoosiers." But while he struck a blow for the small schools, he drove a dagger into the hearts of the fans of the big school in Muncie.

Echelbarger watched that game on television at home, all alone. His parents were watching the game in another home with a large group of friends, because the Bearcats playing for a state championship was the best reason of all to throw a party.

"At that point I wasn't hooked yet," he said. "When Milan won, I called over to talk to my parents and all of the adults there were crying like babies. I'd never heard anything like it. It was like a disaster had happened.

"I suddenly realized this must be for real."

What young boy wouldn't want to be part of such madness? Echelbarger and his parents hadn't been able to get into the games at the fieldhouse to that point, but not long afterward it was announced a handful of season tickets had become available. Five or six, maybe seven. Echelbarger, in fifth or sixth grade at the time, got in line about 7 p.m. the night before to get in line. He recalls being third.

He waited up all night. He might have been given a folding chair to sit in, he doesn't recall. Didn't care. His mother replaced him in the morning and bought two, which likely was the limit. They were together, but they were tickets for seats in the fieldhouse and that was all that mattered.

Going to games only fueled the desire to join the city's most exclusive club, the varsity team. Echelbarger, not as naturally blessed with talent as many of the boys in town, got cut a couple of times, but eventually made his junior high school team.

Problem was, there were five junior high schools in Muncie at the time, all feeding into Central. To become one of 12 members of the junior varsity team – the Bearkittens, they were called – was a major accomplishment. Echelbarger's only way to work on his game in those years he got cut from the junior high school team was to play by himself in a neighbor's driveway. In the winter, that meant shoveling off the snow first.

"People thought I was nuts," he said. "If you weren't on the team, you were alone. I kept working at it and working at it."

When he made the JV team, he thought he had arrived. But that brought new challenges. Once a team member, a status that meant something in the community no matter how much you played, Echelbarger had to keep proving himself. He often went to an elementary school playground to shoot in the summers. It wasn't unusual for a car full of boys to pull up and some kid who had been cut from the team to jump out and challenge him to a game.

"I can't tell you how many times I had to defend my court," he said.

Including the team that lost to Milan in 1954, Muncie has had seven runner-up teams in the state tournament, including Delta in the final year of the single-class tournament in 1997. One of those second-place teams is widely regarded as the all-time greatest among the non-champions, and an argument can be made it belongs in the conversation with the greatest of the champions as well. What other high school team from Indiana can claim a roster that included three future NBA players, another future major college star whose career was ended prematurely by injury, and a future NFL player?

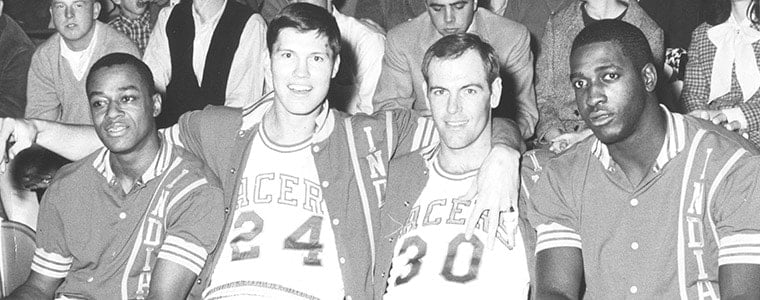

The 1959-60 Bearcats glided through the season without a loss, winning by an average of 32 points. They breezed to a 102-66 victory over a one-loss Bloomington High team in the afternoon game of the state finals, but lost that evening to East Chicago Washington by 16 points in the championship game.

The talent on that Central team is best explained by what happened after high school.

Forward Ron Bonham was a consensus prep All-American and an obvious choice for Mr. Basketball. Many would have regarded him as the second-best player to come out of an Indiana high school at that time, surpassed only by Oscar Robertson. His 40-point outburst in the semi-final victory over Bloomington broke Robertson's final four single-game scoring record by one point. He was a sophomore starter on the University of Cincinnati team that won the NCAA tournament championship in 1962 and was a consensus first-team All-American in 1963 when Cincinnati lost an overtime game to Loyola of Chicago in the championship game. He later played on two NBA championship teams with the Boston Celtics and was a member of the original Pacers team in 1967-68.

Guard John Dampier played two years for a California junior college then averaged 19.3 points as a junior at Miami of Florida. He scored more than 40 points once and more than 30 five times that season, but was overshadowed by future Hall of Famer Rick Barry. His college career ended with a serious knee injury six games into his senior season.

Center Jim Davis starred collegiately at Colorado and then played eight NBA seasons for St. Louis, Atlanta, Houston and Detroit.

Guard Jimmy Nettles became an All-American defensive back at Wisconsin and played five seasons in the NFL.

Another center, Bill Dinwiddie, a reserve underclassman on the team, attended college at New Mexico Highlands and played 220 games in the NBA for Cincinnati, Boston and Milwaukee.

The city could hardly have been more confident of winning another state championship in 1960, but its response to the crushing defeat of the championship game loss was telling. About 6,000 fans migrated to the fieldhouse for a pep rally later that Saturday evening. On Monday, the team rode on a fire truck from the school to the Rivoli Theatre downtown for a parade and an afternoon rally, and a dance was conducted at the fieldhouse that evening. It gathered again for a banquet 11 days following the final game that was attended by 500 people.

Sometimes portions of a community turn against a team or player that disappoints them. Not that community, not that year.

"We never heard any negatives, only sorrow that we didn't win," Bonham once recalled.

The depth of Muncie's basketball talent pool, which made it so difficult for a kid like Echelbarger to earn a spot on even the junior varsity team, was evident by what happened the following year. Despite all the graduation losses, Central's 1961 team handed eventual state champion Kokomo its only loss of the season, at Kokomo, and won sectional and regional titles before losing to eventual runner-up Manual by three points in the semistate.

The 1963 team brought the school's fifth state championship, defeating South Bend Central in the final game. Rick Jones, who led the scoring in the two "final four" games, was later voted Mr. Basketball, although many – Jones included – thought the honor would go to teammate Mike Rolf, who had been the leading scorer during the regular season. Rolf went on to lead the Indiana All-Stars in scoring in each of the two games in the annual series against Kentucky that year, scoring 34 points in the second game in Louisville. He followed Bonham to Cincinnati, where he broke Robertson's freshman scoring record and had three games of more than 50 points.

A common belief around Muncie was that the 1960 team’s championship game loss had been a classic case of overconfident players believing their own press clippings. Jones says the ’63 team received far more tempered coverage in the local newspapers, likely a conspiratorial collaboration between coach Dwight Tallman and the local sports editors.

"We didn't get a lot of ink; they didn't want us to get overconfident," Jones said. "I'm sure (Tallman) said, 'We're going to keep the boys under wraps.'"

The wraps came off for the championship celebration, though. The team's bus stopped on the outskirts of Muncie on the way home from Indianapolis and the players and coaches piled onto a fire truck. "We were sitting there freezing to death," Jones recalled. They were driven to the fieldhouse for a more joyous pep rally than what had occurred three years earlier, and then had their celebration at the Rivoli Theatre on Monday.

The same night the '63 Bearcats were winning the state championship, Bonham could be found a two-hour drive to the south in Louisville, playing for the NCAA championship as member of the Cincinnati Bearcats. The Central team listened to the end of that game on the radio on the bus ride home. Bonham, meanwhile, recalled walking to the locker room at halftime of Cincinnati's game with Loyola and hearing someone shout, "Hey, Ron, Muncie Central just won the state championship!"

Cincinnati held a commanding lead in the second half over Loyola, but became overly cautious and wound up losing in overtime. Bonham led his team with 22 points.

"We thought there would be two Bearcat champions that night," Jones said.

Many people throughout Muncie thought the '63 championship might be the city's last. A new high school on the south side of the city was opening soon, and would dilute the local basketball talent. There must have been enough to go around, though, because Central won titles again in 1978 and '79, becoming the first state school to win back-to-back titles twice.

A pair of memorable point guards led those championships.

Jack Moore scored 34 points in the afternoon game and 27 in the championship game in '78. He went on to play at Nebraska, where he was voted the Frances Pomeroy Naismith award as the nation's best player under 6-foot tall, was first-team all-conference as a senior, finished second in the nation in free throw percentage and was an Academic All-American.

He was killed in a private plane crash in Iowa in 1984 while returning from watching Central play in the sectional.

Ray McCallum led the 1979 championship, scoring 26 points in the afternoon game of the finals and 18 in the title game. He went on to play at Ball State and has been a head coach at Ball State, Houston and Detroit Mercy, as well as an assistant coach at Indiana University.

Central won its record eighth title in 1988. Chandler Thompson scored 32 points in the afternoon victory over a Bedford North Lawrence team led by sophomore Damon Bailey, and 21 in the championship game win over a Concord team led by future NBA star Shawn Kemp.

That team's only regular season loss was in overtime to conference rival Richmond.

Thompson went on to become an all-conference player at Ball State and led the Cardinals to the Sweet Sixteen of the NCAA tournament in 1990, where it lost by two points to eventual champion UNLV. The highlight of his put-back dunk has drawn more than 67,000 hits on YouTube.

Thompson is now the Bearcats' head coach, and in a unique position to appreciate the city's basketball history. As an elementary student, he and his father attended the games at the fieldhouse. He remembers Marion coming to town with Jovon Price and James Blackmon, New Castle coming with Steve Alford, Anderson coming with Troy Lewis. He watched Jack Moore and Ray McCallum lead the consecutive state championships, witnessed the celebratory parades, and dreamed of being part of the show.

Worked toward it, too. On the playgrounds, he and his friends imitated the players they watched perform in the fieldhouse, both home and visitors.

"That was big for me as a kid watching that," he said. "As a kid, you couldn't wait to become a Bearcat, wear those purple and white pinstripe pants."

Even in the Eighties, he and his father had to do what fathers and sons had been doing for decades: get to the game before the Bearkittens junior varsity team took the court so they could be sure of having a seat for the varsity game.

"If you got there just before the varsity game you had to stand," Thompson said. "The seats were slim pickens. You'd have to go all the way up to the tip-top, or, if it was really a big game like Marion or Anderson or a team from Muncie, you'd be in the stairwell."

Muncie Fieldhouse is empty now, still under rehabilitation from the tornado that ripped a hole in its roof and drenched it with water in November of 2017. A date for its return remains uncertain. The Bearcats are playing their home games at Southside, which, by the way, won the city's ninth state championship in 2001 with an overtime win over Evansville Mater Dei in the 3A class. Delta, on the outskirts of the city, won the 3A title in 2002.

Attendance is down for Central games now, for a variety of reasons. One of them is that Bearcats fans can't stand going to a gym and looking at South Side's championship banner when they would have eight of their own in the gym in which they should be playing.

"A lot of people are upset because that one red banner is (in the South Side gym) and think it's an eyesore," Thompson said.

Thompson tries to tell his players about Muncie's tradition. It's difficult for them to understand, because they didn't grow up with it the way Echelbarger, Bonham, Jones, Moore and McCallum did. Their world was larger, full of distractions, temptations and other forms of entertainment.

"I don't think they understand the tradition behind that name on the front of the jersey," Thompson said. "I don't think they understand how it was for us growing up. Everything has changed."

Not the memories, though, and not the ties that still bind. Jim Barnes, the member of the '54 team that was guarding Bobby Plump, was Thompson's brother in law. Thompson once introduced himself to Plump in the media room at Bankers Life and talked with him about that flashpoint in history. Dinwiddie, a sophomore on the '60 team, was his mother's brother. Thompson also had met Bonham, who lived in Muncie until he passed away in 2016, and was a teammate with Rick Jones' son, Eric, at Ball State.

They're all connected. Always will be.

Have a question for Mark? Want it to be on Pacers.com? Email him at askmontieth@gmail.com and you could be featured in his next mailbag.

Mark Montieth's book on the formation and groundbreaking seasons of the Pacers, "Reborn: The Pacers and the Return of Pro Basketball to Indianapolis," is available in bookstores throughout Indiana and on Amazon.com.

Note: The contents of this page have not been reviewed or endorsed by the Indiana Pacers. All opinions expressed by Mark Montieth are solely his own and do not reflect the opinions of the Indiana Pacers, their partners, or sponsors.