by Mark Montieth | askmontieth@gmail.com

September 7, 2013

Editor's Note: Have a Pacers-related question for Mark? Want to be featured in his mailbag column? Send your questions to Mark on twitter at @MarkMontieth or by email at askmontieth@gmail.com.

Part 2 of a 2-part series on Roger Brown's basketball career. Read Part 1 »

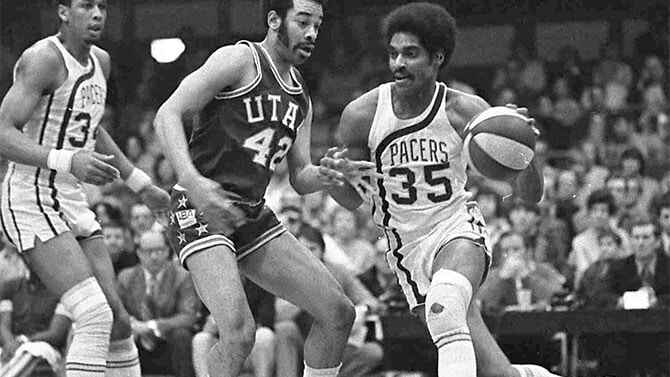

It is a measure of the immense respect his teammates had for his skills and playoff poise that some of Brown's teammates recall him scoring many more points than he did in that game. Daniels has estimated it to be 30, even 40. But those kind of heroics were a fantasy by that point of Brown's career. In fact, that game represented the last hurrah for the core unit that captured the three championships. They won just 46 games the following season and lost to Utah in seven games in the division finals. They fought back to tie the series after losing the first three games, but splattered in the end, losing 109-87 in Game 7 in Salt Lake City. Brown, playing off the bench, led their scoring with 21 in the last game he, Daniels and Lewis played together as Pacers.

But it wasn't the last time they would play together. Storen, who had taken over the Memphis franchise, reunited them there, hoping to milk one last run from them. They looked out of place in the red uniforms of the Sounds, felt no better, and were quickly broken up after Daniels injured his back when he slipped while taking a shower before an early game. In need of another center, Storen traded Lewis for Tom Owens after six games. After one more game, he traded Brown to Utah. Brown played 39 games for the Stars, averaging 9.2 points, and then was waived.

Leonard couldn't bear to see a once-great career end so dishonorably, so he brought him back to the Pacers, who only had to pay part of his contract. Brown was just 33, but was running on fumes. Signed on March 4, he worked his way back into shape and began playing again on the 22nd. He wore No. 1 now, rather than the familiar No. 35, and was clearly a shell of his former self, but still managed some contributions off the bench over the final 10 regular season games and in the playoffs. He scored 12 points in Game 2 of the finals against Kentucky, hitting 5-of-7 shots in 18 minutes, but the Pacers lost the series in five games. Brown's playing career ended in Louisville, where the vastly superior Colonels clinched the title with a 110-105 victory. He played six minutes and hit his only shot, a post-up near the basket.

****

And that was that.

Brown led the Pacers in scoring in just one of those seasons. He was a first-team all-league selection once and a second-team selection twice. He was a four-time All-Star. He is the franchise's fourth all-time leading scorer today, having averaged 18 points a game in the regular season. But like Reggie Miller in later years, he raised his level of play in the playoffs, scoring more (18.7) and shooting better (48 percent from the field and 36 percent from the three-point line).

His overall statistics might not have made him an obvious Hall of Fame selection, given the brevity of his career. He arrived late to the professional game because of his banishment, and left early because of his knees, but his peak-level talent was clearly worthy of the honor. It's unlikely that anyone who played against him in the early 1970s would question his selection. Those who played with him? They can't say enough about him. Such is their admiration for him that they often exaggerate his accomplishments. Daniels' passion for Brown is such that he considers him the best player of all time, short of Michael Jordan.

Brown commanded respect beyond his playing skills, however. To his teammates, he was the cool guy in the room, the guy who only exerted as much energy as necessary, the guy who could get away with a few things from the coach, the guy who never seemed ruffled, the guy who always seemed to produce when it counted most. He was handsome, and had a regal bearing on and off the court. If Miller was a puppy dog, bouncing around the room, all emotional and eager to please, Brown was a cat who sat back, observed, and waited until it was time to pounce.

“He was that guy,” Daniels said. “He was that guy that deep down inside, all of us wanted to be like.”

The downside of Brown's persistent composure was that his effort was lacking at times. In today's media environment, he no doubt would have come in for some loud criticism after some games. Leonard's decision to leave him home for those two road games is an indication of that. Don Hein, who broadcast the Pacers games for Channel 13 during Brown's early seasons with the Pacers, recalled stating that Brown was playing lazily during one road game. Brown approached him the next day and asked if it was true he had said that on the air. Hein said yes. “You were right,” Brown said.

Brown's philosophy of energy conservation was nearly a way of life, extending off the court and to other people. He used to lecture the Pacers' trainer, David Craig, on how to get his chores accomplished in fewer steps.

“He'd say, 'You're working too hard, you need to relax,'” Craig recalled. “That's the way Roger was. He wasn't going to waste any energy. But when it came to basketball, he knew how to play the game with the least amount of energy exerted.”

For that reason, he rarely dunked a basketball. He had been an outstanding high jumper on his high school track team, but rarely showed it with the Pacers. Even on breakaway layups he'd lay the ball up softly off the glass. But he kept it in reserve for special occasions.

“The only time I ever saw him dunk in warmups was our first exhibition game (in 1967),” said Bob Netolicky, another original Pacer. “He did a double windmill, two-handed thing. I couldn't believe it. And that's the last time he did it. He was kind of fired up, his first pro game and all.”

Hillman recalled another time when the players were dunking in pre-game warmups, showing off for one another. Brown wasn't participating, so they began teasing him about being too old. He didn't give in, but during the game threw down a two-handed rebuttal.

“Those of us on the bench all lost it, screaming and hollering and cheering,” Hillman said. “We never saw him dunk again for two or three years after that.”

Brown's greatness was crystallized in his one-on-one moves. He was quick, deceptive and knew how to read defenders. A head-fake here, a jab-step there, and the defender was on his heels. He could then do as he pleased, either take a jumper or slip to the basket. Once he got into the lane, more head fakes and uncanny balance and timing allowed him to get off his shot in traffic. He wasn't fast running up and down the court, but his first step was deceptively quick. Pavy, who has seen all the players that have come through the game since the 1950s, considers Brown's rocker step to be the best of all. It became an essential part of the Pacers offense, and an easy go-to strategy late in close games.

“Get the ball to Roger and let's go drink beer,” Leonard would say in the huddle.

Brown's teammates delighted in such moments.

“It was like, 'Oh, boy, you're about to get schooled. The professor is about to open the book. Learn your lesson now!'” Hillman said of his thoughts toward Brown's hapless defenders. “He wouldn't show all his wares to you. If he had one simple thing to beat you, he'd stick with that. But trust me, if you figured that out, he'd have something else for you. He always had one more thing he could do to extend the play or determine the outcome of the event.”

Hillman also experienced it firsthand. He and Brown, who were roommates on the road, went one-on-one after practice most days for a couple of seasons. Hillman recalls winning exactly two times.

“You had the entire court to use, so Roger would pull up and hit a three-pointer, or pull up and hit a 12-footer, or go to the rim,” Hillman said. “He was uncanny. He just needed a little space to get you off balance and he would read your body language. He would always keep me on my heels, so I couldn't get off the floor in time to block his shot.”

Brown's poise at closing time of games is what impressed his teammates most. Leonard had a favorite saying about playing on the road back then: “Go out there like you own the damn place.” Brown lived that better than anyone. Like Miller, his greatest moments seemed to come on the road, where he delighted in quieting fans.

“You've heard the phrase 'hushing the crowd?'” Netolicky said. “Roger did a lot of hushes. I remember one game when he went around the guy so easily that he was laughing as he laid it up. The crowd just gasped. It went from a roar to quiet. He literally froze the other team and froze the crowd. I can't remember the other team, but I remember it like it was yesterday. I looked over at Slick and thought, Can you believe that?”

For Brown, however, poise included keeping his emotions in check. He rarely let loose with teammates, and was admittedly standoffish with strangers. His banishment from basketball had scarred his psyche. “I would almost be labeled conceited because I wouldn't talk to people,” he told the Star in 1996, a few months before he died. “You just don't know what someone's motives are.”

Brown never complained about his ban publicly, nor did he pound his chest when he and fellow Brooklyn schoolboy Connie Hawkins won their lawsuit against the NBA in 1969. (Hawkins took advantage of the opportunity to jump to the NBA, while Brown stayed put with the Pacers.) Brown rarely mentioned his ordeal to his teammates, and never discussed it at length with any of them. It was mentioned occasionally in the newspapers early in his career with the Pacers, but never reported in great detail – probably because Brown wouldn't cooperate on such a story.

Brown said in later years that the stress of being banned from basketball had caused him to start smoking, a habit he continued throughout his playing career and beyond. Craig wonders if that, along with Brown's manner of keeping his emotions to himself, didn't contribute to the cancer that invaded his internal organs. But all agree that Brown was a great friend once you earned his trust. The fact that he didn't make friends easily made the friendships he did have more meaningful to others.

“Once Roger felt comfortable with you, all of a sudden a shadow was lifted,” Daniels said.

For Craig, who joined the team in 1970, that took about six weeks. Until then, Brown had barely said a word to him.

“He wanted to evaluate a situation, size up an individual first,” Craig said. “Then one day we're on our way to New York for a game and he said, 'David, I want you to go to dinner with me. I want you to meet a friend of mine.' We went out to dinner with this man and he said, 'This is the man who helped me in high school, who took me to the dentist and got my teeth corrected because I was embarrassed, who made sure I had clothing and made sure I was fed.' I was very honored that he would want me to meet this individual.”

****

Craig was talking on the telephone from a restaurant in Kutztown, Pa., a break on the drive he and his wife were making to Springfield for Brown's induction. Brown was that important to him. Leonard and his wife, Nancy, will fly out Sunday morning on a private plane with Pacers president Larry Bird, who will present Oscar Schmidt for induction, and coach Frank Vogel, whose coaching mentor Rick Pitino also will be inducted. Daniels and Miller will be on hand to formally present Roger Brown Jr. and daughter Gayle, who will combine to make the acceptance speech for him. Lewis also is expected to attend. If Springfield weren't so far out of the way and tickets for the ceremony weren't so expensive, many others would attend as well.

Brown's ability to inspire loyalty was most evident as he was dying. He was divorced from his second wife, Jeannie, at the time, but she took him in again so that he could receive hospice care at her home. Many of the Pacers have poignant memories of their final visit with him. Daniels, who had helped him get dressed and taken him to the hospital when Brown could no longer ignore his illness, saw him the day before he died, before Daniels left for a scouting trip. They held hands, shared a knowing look, and Daniels returned the kiss on the forehead that Brown had given him in 1970. Craig also visited that day, and remembers Brown, as always, having no complaints. Leonard and George McGinnis also were there at the end. Jeannie had sliced a banana, and they took turns feeding it to him.

Ultimately, Browns career is notable nearly as much for what he didn't show as what he did. He will always be surrounded by a hint of mystery because of those lost years. He didn't play organized basketball other than AAU games after his freshman season at Dayton in 1960-61 until the ABA was formed in 1967. That's six college and professional seasons with healthy knees. If those hadn't been taken away, Brown likely would have been a college All-American at Dayton and a high NBA draft pick – in which case he wouldn't have been available to the Pacers, the Pacers might not have lasted for more than a few years in the ABA, and wouldn't exist today.

A fatalist would say it all worked out as it was supposed to. That's easy to say now, however, and trivializes the sacrifice Brown had to make.

“It was like they took Secretariat out and put him on a plow for a few years and then brought him back to race,” Netolicky said.

After Sunday, the memories of Brown's career can run forever.

Note: The contents of this page have not been reviewed or endorsed by the Indiana Pacers. All opinions expressed by Mark Montieth are solely his own and do not reflect the opinions of the Indiana Pacers, their partners, or sponsors.