Sometimes things work out in the long run, no matter how agonizing those shorter runs can be. Sometimes you think you were in the wrong place at the wrong time, only to find out those times and places might have protected you from veering off course.

Larry Humes knows this now, but he's challenged to remember it every time he sees the collage of head shots of the members of the inaugural Pacers team, which began play in October of 1967. He walks past it on his way to his usher's station at the top of the steps leading to Sections 17 and 18 in the lower bowl at Bankers Life Fieldhouse, and when he glances at it he feels a twinge of …. of what? Anger? Frustration? Betrayal? Regret? Maybe all of the above. He very nearly made that team, he expected to make that team, and other people believe he should have made that team. He could just as easily be in that photo as not, and he could just as easily be an ex-Pacers player as an usher who directs fans toward their seats to watch the current Pacers play.

The years have worn away the rough edges and brought perspective to Humes, because too many good things have happened in his life to be brought down by a couple of blows to his pride and desired profession. When you were Indiana's Mr. Basketball, a college All-American and member of two national championship teams, a longtime teacher and coach, and a successful husband and father, it's easy to forget the disappointments.

And perhaps learn to appreciate them.

“It works out for the best in the long run,” Humes says. “You can't let anything keep you down.”

Humes' long run began in Madison, perched over the Ohio River, where he grew up the third-oldest of nine kids, eight of them boys. The family squeezed into a two-bedroom shotgun house that didn't have indoor plumbing for Larry's first few years. It scraped by on his father's income as a mechanic and the extra money his mother brought in by doing laundry and ironing shirts for local businessmen. She was well-known within the community for her touch with an iron, and earned 10 cents per shirt. Larry grew up wearing hand-me-down clothes and, when old enough, did odd jobs such as washing windows and polishing stoves to add to the family income.

He soon became acquainted with Madison's rich basketball tradition, and saw a path to a better world. The high school team had finished runner-up by one point to Jasper in the final game of the state tournament in 1949, and then won it by 23 points over Lafayette Jeff in 1950. Humes was six years old when Madison won the championship, and he could see, hear and feel the impact it had on the community. He eventually met some of the players from that team and saw how they were respected, even revered, years after their feat. He dedicated himself to becoming like them.

PHOTOS: Larry Humes Career Gallery »

He was fortunate that Julius “Bud” Ritter, who took over Madison's varsity team in 1954, was waiting on him when he reached high school. Ritter was a progressive-minded coach who not only integrated the program via Humes, he made Humes the centerpiece of his teams. Humes started as a freshman, when Madison lost to eventual 1959 state champion Attucks by two points in overtime in the semistate. He scored 19 in that game. Madison lost to state runner-up Muncie Central in the semistate in 1960 and then reached the Final Four in 1962, his senior season.

It lost to Evansville Bosse in the afternoon game, 79-75. Humes got in early foul trouble and had to sit out much of the game, but still scored 22 points. Bosse went on to win the title that evening by three points over East Chicago Washington.

Madison's record was 97-5 over Humes' four seasons, with only one of the losses coming in the regular season – his freshman season. Beneath the shiny surface, though, some dark realities lingered. Madison's players were treated to a banana split at a local drug store after each homecourt victory. Blacks, however, were still not welcome to dine with whites in the town's restaurants, so Humes made excuses and skipped the outings rather than face the embarrassment of being turned away.

The sting of social norms and the state tournament losses was soothed when Humes was voted Mr. Basketball for 1962 for the annual series with Kentucky. Indiana's All-Star team that year included Jim “Goose” Ligon, who went on to become an ABA All-Star, and Dave Schellhase, who became an All-American at Purdue. Humes scored 21 points in the first of the two-game series, hitting 9-of-12 shots in an 88-82 victory in Louisville, and had 19 in the second game, a loss in Indianapolis.

He received, by his estimation, 45-50 scholarship offers. Ritter helped him narrow them down to four: Purdue, Cincinnati, UCLA and Evansville. All had their selling points. The coach who had led Madison to the 1950 state title, Ray Eddy, was coaching at Purdue by then, and Ritter had played there as well, starting for two seasons. Humes, naturally, had a positive image of the place. Cincinnati was the closest of the four, and had won the NCAA championship in 1961 and '62. It had a history of recruiting Indiana's Mr. Basketballs – Oscar Robertson in 1956 and Ron Bonham in 1960 – along with other players from the state. UCLA coach John Wooden, a Martinsville native, also was trying to import high school players from the state, although without success to that point.

Ultimately, Humes took Ritter's advice to attend Evansville College, as it was known then. It was a Division II school, but routinely played Division I teams. Its arena, Roberts Stadium, was six years old and routinely drew sellout crowds of more than 12,000 fans – not bad for a school with an enrollment of about 2,500. Ritter, an Evansville native, thought it practical for Humes to go there, because he would have a better chance of finding a job after college if he stayed in southern Indiana.

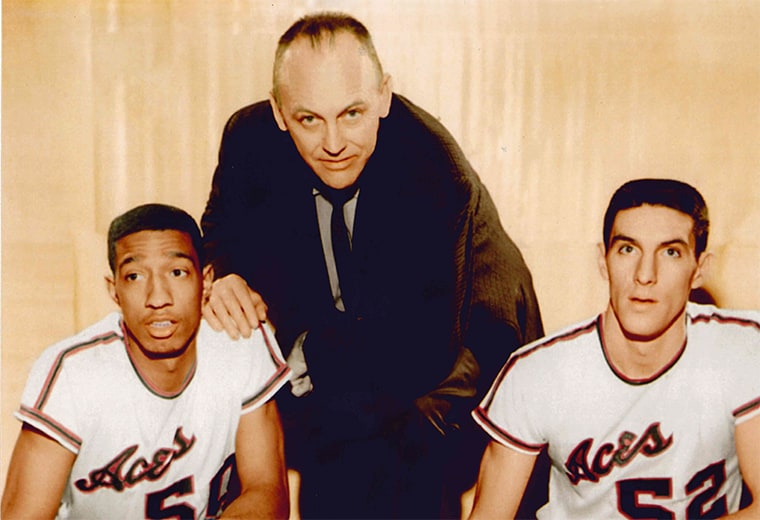

Humes (left) poses with Evansville head coach Arad McCutcheon and teammate Jerry Sloan. (Photo Courtesy of Larry Humes)

Humes' timing was good once again. The Purple Aces were a perennial Division II power under coach Arad McCutcheon, who had already led them to national titles in 1959 and '60, and would win five in all on his way to selection to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. McCutcheon's teams were fast-paced and high-scoring, but played structured offenses in the halfcourt and bruising defense, too. He was known as a tough but funny, fair and grounded coach, one who insisted on teaching math and P.E. classes so he could connect with the entire student body, not just the basketball players.

His teams were fundamental, but had flair, too, both in the way they played and the way they dressed. And oh, how they dressed. They wore short-sleeved jerseys, something they had done since the late 1940s because so many of the fieldhouses in which they played were drafty. Defying their nickname, they wore orange instead of purple on the road because McCutcheon thought the brighter color made it easier for his players to spot one another on the fastbreak, while the lack of contrast between the uniforms and the ball made them more difficult to defend. Most outlandish of all, they wore shiny capes over their warmup tops. Those came courtesy of Gus Doerner, a former Evansville player who owned sporting goods stores in the area, and donated them to the program. They were samples of items sold to boxers, and therefore arrived in a rainbow of colors – blue, green, red, yellow, silver and whatever else Doerner might have left over. They served the practical purpose of keeping the players warm on the bench, and were easy to put on and take off. McCutcheon, meanwhile, had superstitiously taken to wearing red socks, a red vest and a red tie for games, and many of the fans followed suit.

In summary, you had a team called the Purple Aces wearing orange uniforms (on the road) and multi-colored capes playing its home games in a stadium filled with red-clad fans. It all added up to a daunting atmosphere that no doubt helped win games for the not-so-purple Aces. Hall of Fame guard Walt Frazier, who played against them during his college career at Southern Illinois, remembers it well.

“I was coming from Atlanta, where football is king,” he said. “Now I come to Southern Illinois. We go to Evansville, and it was like going to Madison Square Garden. Ten thousand people screaming … and they come out in these boxing robes. It was like being in the Roman Coliseum, man. I was like, 'What is this?' It was intimidating, man. Very intimidating.”

Humes didn't make things any easier for opponents. He was slender and 6-foot-4, and worked mostly around the basket. Still, he developed into a nearly unstoppable offensive force. He became the university's all-time leading scorer after his three varsity seasons with 2,236 points (a 26.4 career average), and held that record until two years ago when Colt Ryan, a four-year player, broke his mark. He set a school single-game scoring record with 48 points as a junior against Ball State. He also recalls having 41 against LSU before he was taken out of a blowout victory with about 12 minutes left.

Evansville won the Division II national championship in 1964 and '65, when Humes was a sophomore and junior. Jerry Sloan, who went on to a Hall of Fame coaching career with the Utah Jazz, was his most prominent teammate, but the Aces had a balanced squad. On offense, Humes played inside while Sloan stayed on the perimeter. They flipped on defense, with Humes taking the guards and Sloan muscling with the bigger players.

Humes' style of play was unique, to say the least. He put up long hook shots and off-balance shots off post-ups, shots that would get a player benched today if they didn't go in often enough. His did. He was a career 50 percent field goal shooter in an era when that was an exceptional percentage. He rarely shot from the perimeter, as his quickness, agility and creativity more than made up for his lack of size around the basket. He and Sloan, who was a year older, both became two-time All-Americans in the small college division.

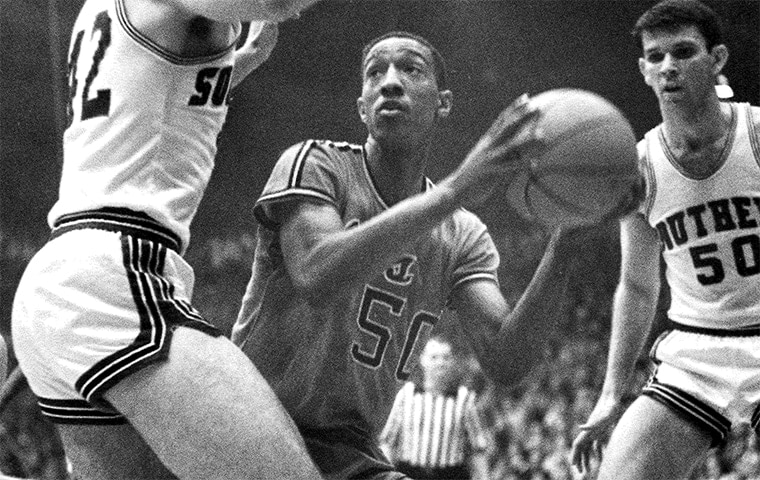

Evansville won the 32-team Division II tournament in 1964 by beating Frazier's Southern Illinois team 64-59 in the regional final, then winning the final three tournament games by an average of 16.6 points. It went undefeated over 29 games the following season, when Humes was a junior and Sloan a senior, and wasted no time proving itself with victories over three Division I programs. It defeated Iowa in the opener, as Humes scored 39. It followed with a win over Northwestern, and then beat a Notre Dame team that would go on to qualify for the NCAA tournament. Humes scored 37 in that one.

The Aces won the Division II title with another win over Frazier's Southern Illinois team in the championship game, on their home court, by three points. Humes led a rally that forced overtime, banking in a 15-foot hook shot from the right wing late in regulation.

“He was prolific, man,” Frazier said. “Uncanny. He was a maestro with the low post. Bank shots, spins, English off the glass … I never saw anything like it. He was phenomenal, man. I couldn't stop him. Hanging shots, off-balance, fadeaway, using the glass … he averaged like 30 a game didn't he?”

Humes averaged 32.5 points to be exact as a junior, and then 31 as a senior when Evansville, without the graduated Sloan, was eliminated in the tournament regional. He finished his career as a two-time All-American, a three-time all-tournament pick and three-time all-conference selection. NBA teams were skeptical, however, of a 6-4 player who hadn't strayed far from the basket on offense, particularly one from a Division II program. He was the 50th overall selection in the 1966 draft, the last player taken in the fifth round, by the expansion Chicago Bulls.

On the surface, it seemed a good thing to be drafted by an expansion team, which would have no star players, but it wasn't. The Bulls had been allowed to sign unprotected veterans from the depths of the other NBA rosters, and therefore had a surplus of players with guaranteed contracts. It didn't help Humes' causes that they also drafted the 6-5 Schellhase, who had gone on to an All-American career at Purdue, in the first round. Schellhase was similar to Humes in that he was having to make a transition from college forward to professional guard. He would wind up playing just 73 games over two NBA seasons. Humes was released in the final cut. He recalls coach Johnny “Red” Kerr telling him that the team simply had too much money tied up in veteran players with guaranteed contracts to keep him, but that with another year of experience he would have a good chance to make an NBA roster.

But where could he get that experience? Humes was married and had a son by then and wanted as stable a lifestyle as possible. He was offered a contract to play with a team in Italy, but European basketball wasn't nearly as established then as today. He also could have played for the Globetrotters, but he only wanted to play “serious” basketball. In either case, he would have been away from home far too often. He wound up landing a job teaching physical education and health at IPS School 101 with the help of Bill Malone, his former grade school teacher who was a principal in Indianapolis at the time.

He seemed to get another break when a professional basketball franchise was formed in Indianapolis in a new league, the American Basketball Association, in 1967. Humes became the third player signed by the team – or at least the third one to be announced – and his reputation was big enough to merit a headline in the Indianapolis Star and a feature article in the Indianapolis News. He signed a non-guaranteed contract for $10,000 with a $2,000 bonus. He recalls going to the bank, cashing the bonus check, taking home 100 $20 bills and spreading them out on the bed with his wife.

“We were on Cloud Nine,” he said.

And why not? The news release on May 18 to announce Humes' signing had an air of certainty about it.

“Larry will certainly be an asset to the squad,” General Manager Mike Storen was quoted. “He represents the type of players we hope to use in forming the team. He is an exciting player, has tremendous ability and this is what we are seeking.”

The release went on to claim that only 20 new players had made NBA rosters the previous season, and Humes was an example of those who were good enough to play professionally but had not yet found a home. The release also quoted McCutcheon as claiming Humes “could possibly be one of the best players with the Indiana club this year.” Finally, Humes was quoted: “The Indiana club will be a real sports attraction and I am proud to be a member of the ball club.”

Humes was so optimistic about his chance of making the team he moved his family to a house on Winthrop Ave., a short drive from the Fairgrounds Coliseum where the Pacers would play their home games. He worked out twice a day to prepare for his opportunity, and for a while it did indeed look like he had it made – both the team and the life he wanted.

He participated in an open tryout session in June that drew dozens of dreamers, some who had been signed to contracts and some who walked in off the street. After the crowd of contenders was thinned out with grueling practice sessions, public scrimmages were conducted. Bob “Slick” Leonard and Clyde Lovellette were brought in to run the workouts and coach the games, while the Pacers' head coach, Larry Staverman, sat back and surveyed the potential talent. Leonard singled out Humes for praise in one newspaper article early in the proceedings, and Humes later backed up that opinion by leading a team coached by Leonard to a victory in the third intrasquad scrimmage with 18 points before 3,000 fans at the Fairgrounds Coliseum. (Leonard, who was selling class rings for Herff Jones and living in Kokomo at the time, had been called in to help with the tryouts, as was Lovellette, another Indiana high school star with NBA playing experience.)

Four scrimmages in all were conducted, and Humes finished with the third-highest scoring average (13.0), while hitting 54 percent of his field goal attempts. Roger Brown (14.7) and Bobby Joe Edmonds (14.5) were the only players to score more. Humes was among 15 players invited to participate in a series of summer workouts at the Jewish Community Center, and then was one of the players invited to the Pacers' training camp at St. Joseph's College in Rensselaer, Ind. that fall.

He played in the first two exhibition games against the Minnesota Muskies, going scoreless in the first and scoring five in the second. He and Marshall didn't play in the final four games, although Humes recalls spraining an ankle in the second game and being held out of a couple of games for that reason. Still, he was “shocked” when he didn't survive the final cut. He thought he had played well enough to make it. So did Leonard, based on what he had seen in the summer scrimmages.

“Yeah, he should have made it,” Leonard says today.

Why didn't he?

“I don't know,” Leonard said. “They made the decision. I think they had some guys signed to contracts.”

They did, indeed, just like the Bulls the previous year. Freddie Lewis, who had played one season with the Cincinnati Royals in the NBA, and Jim Dawson, who had been the Big Ten's Most Valuable Player at Illinois in 1967, had guaranteed contracts. Jimmy Rayl, Indiana's Mr. Basketball in 1959 and a high-scoring guard at IU, had been signed in August and had an advantage because of his heritage and ability to hit the ABA's three-point shot. Bonham and Brown, at 6-5, were regarded as swingmen who could play guard. That left one spot open for another guard, and Humes, Jerry Harkness and Hubie Marshall out of LaSalle fought for it.

Harkness had been the captain of Loyola's 1963 NCAA championship team, and played briefly for the New York Knicks in the NBA. He had made a memorable impression on Pacers management by writing a letter to Star sports editor Bob Collins to ask for a tryout, and gave up a good sales job with Quaker Oats in Chicago to take a shot at making the team. After struggling in the June scrimmages, he worked out hard the rest of the summer, taking part in the practices and swimming at the YMCA. He caught Staverman's eye by winning all the sprints when training camp opened. He also had a long relationship with Brown, who already was distinguishing himself as the team's most talented player, which didn't hurt.

Marshall was a scorer, like Rayl, and realistically had little chance to beat him out. Harkness and Humes, meanwhile, were similar players – athletic, hustling and defensive-minded, but only average perimeter shooters. Picking one over the other could have been a virtual toss of the coin, and Harkness won.

“It must have been really, really hard to make that final decision,” says Harkness, who burst into tears of joy when he was told he had made the team. “He scared me to death. I was really worried about him. He was such a hard worker, he was aggressive, he did well under the boards and we were similar in a lot of ways. I thought he shot a little better than me. I didn't know which way it was going to go.”

Humes' lack of experience playing on the perimeter in college worked against him. He was having to adjust his style of play on the fly. Leonard believes he could have done so if given time, and Harkness agrees.

“I could see him getting better at the guard spot,” Harkness says. “He was shooting a little better out there and I didn't like that.”

Humes was devastated by his release. It seemed like a dream come true to play professionally in the state in which he had been named Mr. Basketball and helped lead a college to two national championships. He had come so close to making the team, and his reputation was such within the state, that Storen felt obligated to provide an explanation.

“We were very disappointed Humes was unable to make the ballclub,” Storen said. “We hope Larry will get picked up by another team, because we think he deserves a place in the league. He has a lot of basic ability and desire, but he didn't fit into the overall program with our other guards.”

It would be a few years before the heartbreak wore off enough for Humes to begin attending Pacers games with his wife, and even then it was difficult to shake the feeling he should have been in the game, rather than at the game.

“It was hard,” he said. “I knew I should have been out there.”

It was too late to get another teaching job after he was released by the Pacers, so Humes worked an office job for the state highway commission for a year. He then went back to high school teaching and assistant coaching positions, first at Shortridge for five years and then Howe for five years.

He was hired as an assistant coach at Evansville in the summer of 1977. The Aces' new coach, Bobby Watson, wanted to recapture some of the university's tradition, and thought Humes would be an effective recruiter in Indianapolis. Humes signed a contract for $9,000 and began recruiting in the area, while looking for a home in Evansville on the side. In August, however, he was offered the head coaching position at Attucks. His long-awaited opportunity to become a head coach was too good to pass up and his wife had not yet moved out of their home in Indianapolis, so he took it.

Had he not, he would have been on the Evansville team plane that crashed shortly after takeoff in December of that year, killing all those aboard.

Humes coached at Attucks for 10 years, until the school was closed. He then became an assistant coach at Indiana Central (now the University of Indianapolis), first under former Pacers guard Billy Keller and then under Bill Green. He taught P.E. classes on the side, and waited for his turn to become a head coach again.

“Larry's a very likable guy,” Keller said. “A funny guy. He kept everything lively. He truly enjoyed the game. He liked being around people and he loved being involved.”

Humes thought he would become the Greyhounds' head coach after Green retired, but was passed over for Royce Waltman. Humes could have remained as an assistant on Waltman's staff, but that felt like an insult after he had waited his turn. Waltman went on to have immediate success with players Humes had recruited and wound up with the second-best winning percentage in school history. Humes, meanwhile, returned to Attucks' junior high school to finish his career in education. He retired in 2005, after teaching and coaching for 35 years in high school and seven years in college.

With more free time, Humes and his wife occasionally attended Pacers and Fever games. After awhile he befriended one of the ushers, Larry Summers, who began trying to convince him to join the staff. Humes hesitated, but finally gave in four seasons ago. He had retirement hours to fill and the right personality for working with the public, so why not? He got his green jacket, striped shirt and bow tie and began clocking in and out for $10 per hour for Pacers games and other events. After paying for parking, he earns about $35 per game.

It's not about the money, obviously. He doesn't even ask to work every game. But it keeps him active, and keeps him near basketball. Many of the season ticket holders in his sections have gotten to know him, and some have learned of his history. He'll talk about it if asked, but he doesn't volunteer.

“I just kind of keep it quiet,” he said. “If they know fine, if they don't know, fine. I'm like everybody else.

“I'm just down there because it's good people down there. It gets me out of the house, I can talk basketball and I see a lot of older people who know me.”

Leonard, for example. The entrance from the main concourse into Leonard's radio broadcasting position is two sections over from Humes' station, no more than 30 paces away. So close, yet so far. The two talk frequently. More than once, Humes has told Leonard he came along as the Pacers' coach a year too late. Had he coached them from the beginning, he probably would have kept Humes.

Others from the basketball world remember, too. Humes once worked a game outside a suite where former Pacers players were gathered. Jim Morris, the Pacers' president at the time, introduced Humes to Darnell Hillman as one of the greatest players ever to come out of the state of Indiana. Oliver Darden, a starting forward on the first Pacers team, offered an unexpected endorsement, too.

“Larry, I was shocked when they let you go,” Humes recalls Darden telling him. “You really got screwed. I always wanted to tell you that.”

Humes shows his national championship ring to an interested fan. (Photo: Taylor Ward)

Today, Humes rarely thinks of the sour memories … not getting to eat a banana split with his high school teammates, getting cut by the Bulls and Pacers, the head coaching opportunities that didn't come … because there's too much to celebrate. Earlier this year, he attended a 50th anniversary reunion of the members of Evansville's undefeated national championship team, Sloan included. And, in 2012, Elm Street, where the Humes family lived, was renamed Humes Way. As it turned out, Larry was just the beginning of a long line of Humes brothers to play for the high school teams. From 1959, when he was a freshman, to 1977, when the youngest son Charles graduated, every one of them included at least one Humes.

After Larry, the best player in the family was Willie, who attended Vincennes Junior College and then Idaho State. Willie averaged 31.5 points over his two seasons in Idaho from 1969-71, scoring 51 in his debut and 53 in another game. He's a member of the school's Hall of Fame.

The line connecting Larry and Willie draws progress. Back in the ‘70s, Larry applied to be the head coach of Madison's boys' basketball team, but was turned down. The school just wasn't ready for a black coach, he was told privately. In 2011, however, Willie was hired to coach the girls' team. He revived the program, leading his teams to a 54-16 record over three seasons, along with two sectional and one regional title, and a Final Four appearance. He then stepped down voluntarily and returned to Columbus East as an assistant coach, the position he held before going to Madison.

Looking back, Humes can see that even some of his greatest frustrations might have been blessings. In the long run. A professional basketball career can be hard on a man's body, and on his personal life, too. Some of the Pacers from those early seasons wound up getting divorced and unable to be part of their children's daily lives, casualties of the lifestyle of celebrity athletes. Humes has thrived in that regard. He and his wife, Cecele, his high school sweetheart, will have been married 51 years in May.

Their son, Larry Jr., graduated from Indiana Central and works for the Marion County Health Department, supervising after-school programs. His daughter, Shannon, received a PhD in Pharmacy from Purdue and lives in Dallas.

It has become easier and easier to walk by that photo of the first group of Pacers players, the one that doesn't include him.

“I wouldn't change it now,” he says. “There's always a reason for a lot of things, but at the time you don't realize it. (Getting cut by the Pacers) might have been the best thing that ever happened to me. In the long run, I've gained by being with (Cecele) so many years.”

He's also benefited financially. Humes' salary with the Pacers that first season would have been $10,000, not much more than what he made in his early years as a teacher. He would have had to stick with the team a few years to make significantly more. Today, he receives a teacher's pension while the former ABA players are fighting to become part of the NBA's pension plan, in the belief the merger agreement between the leagues in 1976 called for them to receive payments.

Humes has a strong family unit, all the comforts he needs, time on his hands and the respect of his peers who saw him play. That group includes Harkness, the man who beat out him out for a playing career with the Pacers, but who lasted barely more than one season himself.

“Larry is a really good guy,” Harkness says. “We got along great, even though we knew we were competing against one another. You find guys who aren't like that; they don't want anything to do with you. But not Larry. He's just a really good guy.”

Ultimately, that's it's own reward. And not the worst legacy.

Have a question for Mark? Want it to be on Pacers.com? Email him at askmontieth@gmail.com and you could be featured in his next mailbag.

Note: The contents of this page have not been reviewed or endorsed by the Indiana Pacers. All opinions expressed by Mark Montieth are solely his own and do not reflect the opinions of the Indiana Pacers, their partners, or sponsors.