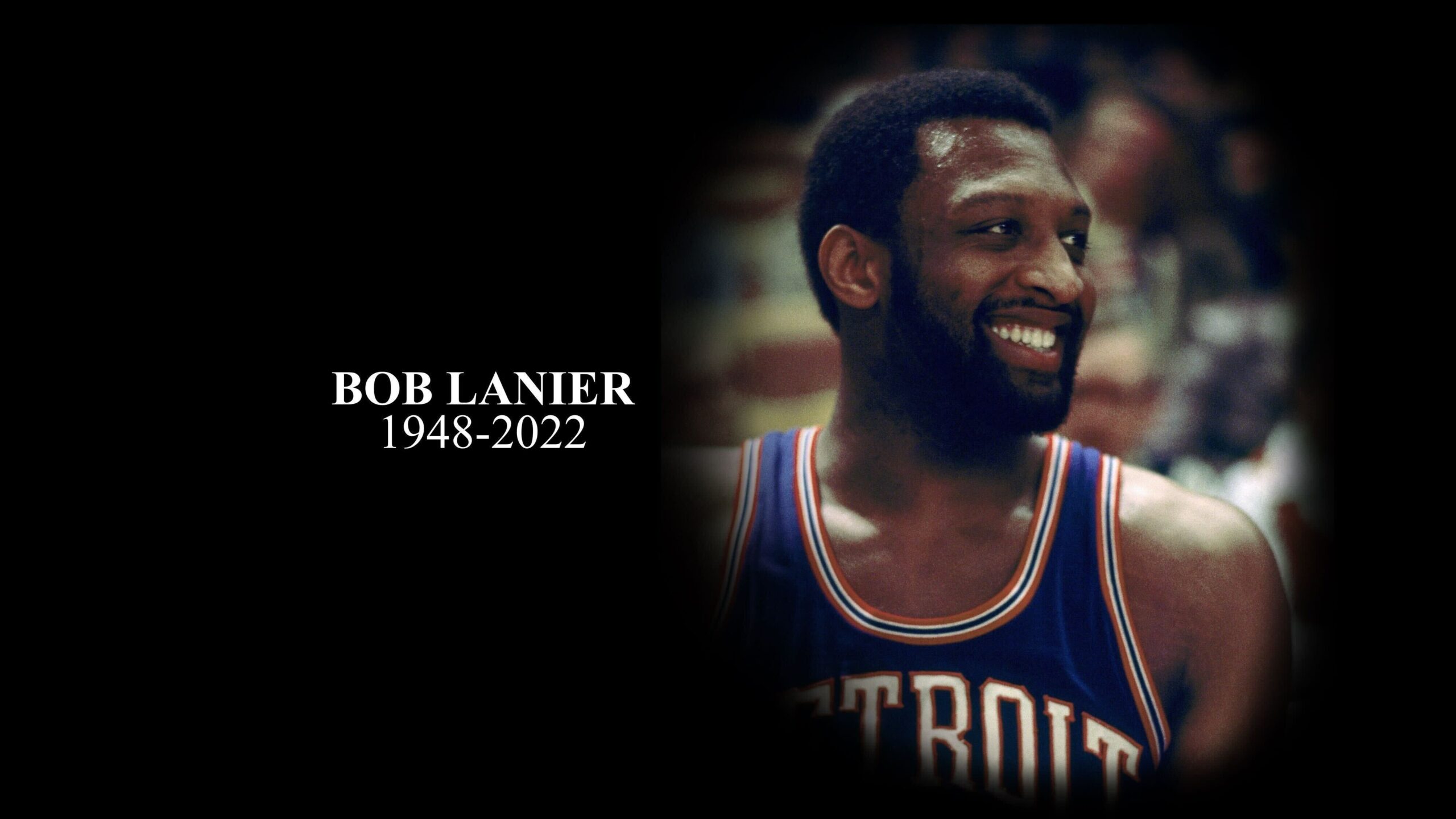

From Hall of Fame player to Global Ambassador, Bob Lanier was part of the NBA family for over 50 years.

MILWAUKEE — The arena went dark Friday night, save for the scoreboard that glowed with a portrait of NBA legend Bob Lanier, who died a few days earlier at age 73. As the PA announcer read an abridged list of the Hall of Famer’s accomplishments, a shot of the rafters at Fiserv Forum showed Lanier’s banner, his No. 16 jersey retired with the dates “1980-1984” beneath it.

Five seasons — not even, considering Lanier arrived in February 1980 via a trade with Detroit. Less than 30% of his 959 NBA games and at the wrong end, his knees already barking at him from his first full nine seasons in Detroit.

Remember that line in “Airplane!” by co-pilot “Roger Murdock,” as played by hoops superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, pulling back the curtain on his true identity? “Tell your old man to drag Walton and Lanier up and down the court for 48 minutes,” he told little Joey. Well, Lanier’s knees had to drag all 6-foot-11 inches, 250 pounds of Lanier up and down the court for as many minutes as they could take it.

So make it five gimpy seasons for Lanier in Milwaukee, skimpy in quantity for appearances and by his standards stats but serious in quality for his impact on the team, the franchise and the relationship with the city.

Lanier, acquired for disappointing 1977 No. 1 pick Kent Benson and a future draft choice, stepped into a Bucks locker room with a pair of young stars in Marques Johnson and Sidney Moncrief and a colorful coach in Don Nelson. But he quickly became a spokesman for and soul of that team, helping to launch them on a stretch of 12 consecutive playoff berths, seven straight division titles and their claim as the fourth-best NBA contender in the 1980s behind only the Los Angeles Lakers, Boston Celtics and Philadelphia 76ers.

The Bucks’ problem was failing to get past both Larry Bird’s and Julius Erving’s teams in the same postseason, which precluded them from facing Magic Johnson’s. But it wasn’t for lack of trying, most poignantly by Lanier.

The big man with the legendary size-22 sneakers clearly played his best basketball the Detroit Pistons, who also have retired his number and where he made eight of his nine All-Star appearances. He impacted a bunch of other places and people, too, owing to his years as an official NBA “ambassador” promoting the league for more than double the time he logged as a player.

But for his work on the court and in the community, for becoming the “old head” on that Bucks team and for his role in bridging the post-Kareem, pre-Giannis championship eras in Milwaukee, Lanier in his brief time there established himself as one of the franchise’s greats.

The applause after the moment of silence, from many fans who weren’t even born when the big man played his last game 38 years ago, was proof of that.

Below are some anecdotes and personal recollections from his time in Milwaukee. I was just getting started on NBA coverage, working for the Milwaukee Journal (pre-merger afternoon newspaper) when Lanier got to town. Writing features and then columns about the Bucks and the league, I got to know him. But Tom Enlund, our intrepid beat writer, really knew Lanier from waiting at the gates of commercial flights teams and media shared back then, grabbing beers after games and generally commiserating across an age gap of only a few years.

Fortunately, I was able to recruit Enlund to share some stories here, too.

When Lanier got to Milwaukee, I knew four things about him: He had played in college at St. Bonaventure, putting that school on the map before suffering a broken leg in the 1970 NCAA tournament that might have cost the Bonnies a championship. He was reputed to wear the biggest sneakers in sports. He had won a gimmicky 1-on-1 tournament ABC taped for halftime segments during the 1972 season, Lanier beating Boston’s JoJo White in the final.

And he had been dubbed something of a loser during nine-plus seasons with Detroit, a seven-time All-Star whose 23 points and 12 rebounds for nearly a decade barely made a ripple in the standings or the playoffs. Assorted injuries got him labeled unfairly as something of a malingerer too.

Didn’t matter to the Bucks, who saw a chance to upgrade at center when that position still dominated. The deal might have triggered weeks earlier but for Lanier’s broken little finger on his left hand. It finally came over All-Star weekend, where Lanier bumped into the Bucks’ Johnson in a hotel elevator. They teased each other about who was going to pass the ball to whom, then Lanier slipped comfortably into the void.

Bob Lanier was acquired by the Bucks during the 1979-80 season.

The impact was immediate. Milwaukee won six straight and 11 of 13 with Lanier aboard. His presence in the inside-out league opened up space for slashers Johnson and Moncrief and shooter Brian Winters. In all, the Bucks went 20-6 after adding Lanier, with the six losses by a total of 13 points.

Lanier’s nickname throughout the NBA back then was “Dobber.” But Enlund knew him by the handle Lanier used when referring to himself: “The Almighty Wondah.”

Amusing as that was, it did little to ease the aches and pains in Lanier’s nagging knees. On his best days, he moved gingerly with two tan rubber sleeves over those surgically repaired knees. And the best days weren’t many.

After a particularly painful and unproductive game in Phoenix in 1982-83, Lanier announced only half-jokingly in the visitors’ dressing room: “I’m retiring. This is the end of the Wondah.”

After the game Lanier and Enlund drove around Phoenix in the player’s rental car. Through a McDonald’s drive-thru. To a local night club. Back to his hotel room where he had some wine on ice. The entire night, his knees were constantly on his mind.

The Bucks went to Houston the next day but Lanier went home to Milwaukee and the injured list. He played only 39 regular-season games, literally on his last legs. But he wasn’t quite done.

An early glimpse of Lanier’s people skills and ambassador potential came on an idle afternoon in Atlanta, killing time at the shopping mall that connected the Omni Arena to the Omni Hotel. Lanier was approached by a group of kids who wanted an autograph and answers to the usual questions: How tall are you? Are you going to beat the Hawks? How big are your feet?

Lanier patiently answered the questions that, had they come from adults, he would have ignored.

“Kids need someone to look up to,” he said.

Lanier returned to action two weeks after that Phoenix scare, driven to play through his injuries by the ring he still felt compelled to chase.

“I’m going to live and die with that dream,” he said. “Because I could never live with myself for the rest of my life if I didn’t feel that I gave my best shot at winning the title. That would bother me for the rest of my life. It would cause me unrest deep in my soul.”

Milwaukee won 55 games that season, then faced the Bird-Robert Parish-Cedric Maxwell Celtics in the conference semifinals. Improbably, they stunned that powerhouse 4-0. After the finale, Lanier was on the floor for a courtside radio interview that was carried over the PA system. He wound up leading the elated fans in an impromptu “Sweep” chant.

Bob Lanier was a key reason why the Bucks were able to power past the Celtics in 1983.

“I can’t describe it,” Lanier said after finally winning a seven-game series in his 13th season. “I’m in a dream trying to figure out if this is all real. If I’m asleep I don’t want to wake up. I can’t explain the depth of what I feel. I can’t put it into words. I feel like crying. I don’t understand it. I’ve got a lot of emotion in me.”

This was, of course, Philadelphia’s championship season. The only thing standing between Hall of Fame center Moses Malone’s “Fo’, fo’, fo’,” prediction and “Fo’, fi’, fo’” reality was the Bucks’ 100-94 victory in Game 4. And the key to that was Lanier mustering the grit to score 17 points in what was the second of back-to-back playoff games.

“You [reporters] don’t realize what guts old people have,” Lanier said. “Reaching down. That’s what the Wondah did.”

Bob Lanier returned to play in 1983-84, his final NBA season.

That summer, Lanier underwent two knee surgeries, his status for the 1983-84 season still uncertain. His decision to come back came on a rainy September afternoon in the driveway of his home in the northern Milwaukee suburbs.

“I drove up to my house one day, there was a basketball in the driveway and I stopped to get it out of the way,” Lanier related. “It was raining, but I thought ‘What the heck?’ and I took a shot. I couldn’t believe it. I shot the ball and it didn’t hurt a bit.

“I ended up shooting for about half an hour. The neighbors were staring at me out of their windows, and people were looking at me as they drove by. But it was such a satisfying feeling to be able to do that I didn’t want to stop.

“I felt like a little kid that day out in the rain,” he said.

The Bucks won 50 games in 1983-84, and one of Lanier’s highlight nights came against New York on Feb. 8. Bernard King poured in 35 points for the Knicks, but Lanier, again laboring through the tail end of a back-to-back, scored 12 in critical moments to spark a 113-103 victory at the MECCA.

“Nah, you won’t see anything about me in the papers tomorrow,” Lanier told me, even though I was talking to him precisely to put something in the paper. “Why? Because those other guys get the points.

“But night after night, when you need the big plays, who makes ‘em,” he continued theatrically. “Old folks make ‘em. Old folks make ‘em.”

Lanier’s final game came that spring, a 115-108 defeat at the Boston Garden as the Celtics eliminated Milwaukee 4-1 from the Eastern Conference finals.

The big man sat down with 44 seconds left after scoring nine points with five rebounds in 32 minutes. He lifted his left wrist band and wiped off the stick-um he always hid there. Postgame, he hinted he was done playing but said nothing definite.

Enlund walked alongside Lanier out of the Garden, running into an old relocated teammate from their Pistons days. M.L. Carr and Lanier talked briefly, then parted.

Riding down the elevator to street level, Lanier boarded a nearly empty team bus. I recall him asking me a question completely unrelated to that game or the league. After several minutes, the Almighty Wondah said loud enough for the driver to hear, “Let’s rock,” and the bus pulled away from the Garden.

Lanier announced his retirement at an emotional press conference at the Milwaukee Hyatt on Sept. 24, 1984.

“It’s been a difficult decision,” he said. “I’ve played basketball for quite a number of years. I’ve had to deal with a lot of pain and aggravation. I had to find out if I could put up with the trauma, physically and emotionally in quest of the all-elusive ring.

“I look at my career and I’ve achieved a lot of my individual goals. When I came to Milwaukee my chances [for a ring] were as good as any time in my career. I wish I would have been here when I was younger and could have been more productive with the players I had around me.”

Nelson, the Bucks coach, knew what even the gimpy Lanier meant to a team that would average more than 52 victories across a dozen seasons. “He made us instant challengers,” Nelson said. “Ever since we acquired him, we considered ourselves among the top four teams in the league.”

Lanier was asked at one point to “describe Bob Lanier.” “I don’t understand him myself,” the big man said. “He’s a complex person. He wears many hats.”

Shaq, Kenny, Ernie and Charles share some fond memories of the late Bob Lanier.

One final anecdote courtesy of Enlund: Lanier showed up as a “special assistant” in the fall of 1984 for Bucks training camp at Marquette University’s old campus gym. Nelson put him in charge of a grueling one-minute defensive sliding drill, and that drill was wearing out the players.

“Twenty-five more seconds,” Lanier yelled at one point, peering at his wristwatch.

“Twenty more seconds,” he barked, continuing to gaze at the watch. “Push it. Push it!”

By now, grimaces were etched onto his former teammates’ faces, but the drill dragged on.

“Ten more seconds,” Lanier said, still staring at his watch. “Give the Dobber ten more seconds.”

With some players ready to collapse, Lanier counted down the final seconds and finally blew his whistle, ending the drill that lasted far longer than the originally announced “minute.”

Might have been due to the Almighty Wondah’s wristwatch having no seconds hand.

* * *

Steve Aschburner has written about the NBA since 1980. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.