LAS VEGAS – The stakes are low. The atmosphere, casual and relaxed. The urgency that hounds NBA coaches daily for most of the calendar year – the next play, the next basket, the next decision, the next opponent – barely makes it to town for the Summer League basketball.

“Working vacation” might be stretching it, but those guys rarely look or act more rested and content. They amble in and out of games at the two gyms on the UNLV campus. They sit up in the stands while a trusty assistant works the sideline for their teams’ summer entries. And they schmooze for hours with friends and rivals, their dukes down, their motors on idle.

Six months ago, though? Six months from now? Forget it. All the demands, all the pressures, all the work undone seize up on them. It’s long hours, heavy pressures, bad diets and worse habits.

“It’s always in the back of your mind,” Denver coach Mike Malone said. “Stress can do a lot of damage, and this job is a very stressful job.”

Malone, at that moment, was filling out paperwork in advance of a free health screening set up Thursday and Friday by the National Basketball Coaches Association [NBCA]. It was a new program at Summer League this year that the NBCA intends to provide annually for head and assistant coaches, a benefit of membership in a profession that almost necessitates it.

“During the season, there’s ups and downs with your health,” Minnesota assistant coach Andy Greer said after his screening and results review was over. “I don’t take care of myself as well as I should. In the offseason, I try to get caught up and make sure that no damage is done.”

It’s always in the back of your mind. Stress can do a lot of damage, and this job is a very stressful job.

Nuggets coach Mike Malone

Problem is, the NBA offseason has been getting shorter while the season seems to get longer.

Several head coaches have had to step away from the grind in recent seasons: Golden State’s Steve Kerr, 52, was coping with a spinal issue when he yielded to assistant Luke Walton for the first 43 games of 2015-16.

Cleveland’s Tyronn Lue, 41, tapped out for 15 days this spring while suffering from anxiety and other effects of stress, including sharp chest pains that were found not be related to his heart. Lue has changed his diet, began exercising more regularly and was prescribed medication.

And new Orlando coach Steve Clifford – who had a heart scare in November 2013 that cost him only one game in his first season with Charlotte but required two surgically placed stents – got sidelined for more than five weeks on the Hornets’ schedule last season by severe headaches that his doctors linked to a chronic sleep shortage.

“My body was telling me, ‘You can’t do this,’” Clifford, 56, said while watching his Magic squad Thursday. “When you start reading about sleep, some of the stuff can scare. Just how it affects your general health.”

Said Greer, who also has served on staffs in Toronto, Chicago, Memphis, Houston and New York: “I’m going to be 56. I owe it to my family to be healthy. I had a mini-stroke one time. I’ve had high blood pressure and high cholesterol. I monitor it and try to do the best that I can with it. But this is awesome.”

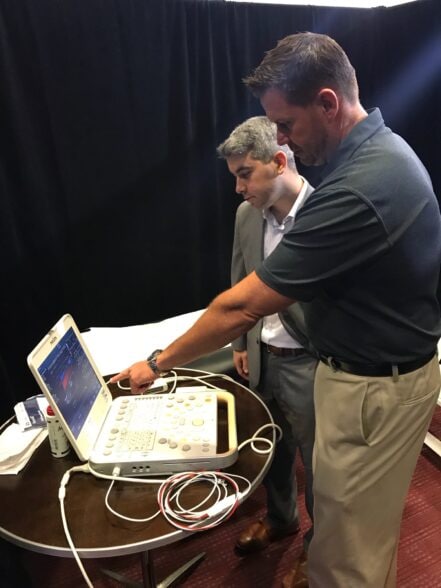

Approximately 60 coaches underwent screenings over the two days. The coaches met with health professionals in the upper level of the Mendenhall Center, and went through a series of stations and tests that included an electrocardiograph, an echocardiogram, a carotid ultrasound, blood work, an orthopedic scan and consultations with a cardiologist and an orthopedist.

The service was contracted with Athletic Heart, an Orlando-based company that provides mobile testing to sport-oriented clients. CEO Wes Stokes mentioned a variety of NCAA athletic programs and professional sports franchises that utilize Athletic Heart. The firm has worked with various leagues’ players unions, as well as the retired players associations in basketball and football.

“If these guys had to go do this on their own,” Stokes said, touting the convenience of geographically bringing the health care to the patients, “this would be three or four days probably of doctors’ appointments, plus all the scheduling and commuting time. And probably cost them thousands of dollars, depending where they went, given the number of doctors and follow-ups they’d see.

“So many of these guys here walk out thinking it’s great. The ones who didn’t show, for whatever reason, will hear it from this group. And next year, they’ll come in.”

The concerns about health have been heightened in the NBA in recent years by the deaths of a number of alumni, in some cases well before traditional life expectancies. Among them: Moses Malone, Darryl Dawkins, Anthony Mason. Last week, Clifford Rozier – a first-round pick by Golden State in 1994 – and former Seattle forward Lonnie Shelton died of heart attacks. Rozier was 45, Shelton 62.

Another benefit of this program is generating electronic medical records for the coaches that can be accessed and updated whenever, wherever.

“So if they leave one team and go to another,” Stokes said, “or have a house in Florida but are out in California, their records are with them all the time. Think of it like a medical passport that you can have with you wherever you go.”

Information about each coaches’ family health history, and current medications, also is included. And while the coaches reviewed their results with the health professionals on site, Stokes said Athletic First has physician’s assistants who will contact them quarterly or so to verify the action plan discussed.

“We had one test today – checking your carotid artery – that I’ve never had done,” Indiana assistant Dan Burke said. “That’s the main reason I went in, just to find out what that is. They said mine was clear, so … okay.”

Burke, 59, said the Pacers have their coaches, like their players, undergo full check-ups before each season. That means stress tests, physicals and meetings with the team’s nutritionist. And head coach Nate McMillan had his whole staff participate in the Vegas screenings.

“I’ve always felt they’ve had our backs on that,” Burke said. “But you can see where the lifestyle, a routine, could put that out of whack. You could easily skip on sleep, skip on exercise. Take the fast track food-wise.

“My dad was a guy who always said, ‘You only need three hours of sleep.’ And I kind of lived by that for a long time. My first few years in the NBA, when I wasn’t sleeping at all, I finally felt, ‘Man, what am I doing?’”

Bulls coach Fred Hoiberg did not get screened this week, only because he submitted to one for former NBA players at the scouting combine in Chicago in May. Hoiberg was only 32, still active with the Timberwolves and had just led the NBA in 3-point percentage in 2004-05 when he got a health scare with which he has lived ever since.

“I went in for a routine life-insurance exam and that’s how I found out I had a ticking time bomb in my chest,” said Hoiberg, who was diagnosed with an aortic valve issue. “I was in the best shape of my life at that time, but I had a life-threatening condition that I needed open-heart surgery to correct.”

Hoiberg, who subsequently had a pacemaker inserted, probably is more informed and conscientious about his health than a lot of generally healthy coaches. He doesn’t wear a necktie during games to avoid any tightness or constriction of blood flow. Still, his screening in May, he said, revealed some blood numbers that had crept up; he has been encouraged to cut back on red meat.

The health screenings, along nutrition, sleep and stress management info provided more readily these days by teams and by the NBCA to its members, are a great start. Ultimately, it’s on the coaches to heed the advice and embrace some changes.

“It’s about routine, about being organized,” said the Pacers’ Burke, who has learned to give himself mental getaways from the job’s demands.

“The last few years, I try to pick up something to teach myself,” he said. “Lately it’s been fly-fishing. I’ve been tying flies. It’s a good release. When I’m home, I try not to even talk about work. Before that it was grilling techniques, cooking up some ribs and rotisserie chicken, just trying to dive into one new thing each summer.”

Malone, 47, is the son of longtime NBA coach Brendan Malone, so he grew up seeing the demands of the profession and how his father coped.

“You have to have an outlet and you have to have balance to give yourself the best chance to stay healthy,” Malone said. “You have to find time to exercise. You have to make sure you’re eating right. The travel, the late nights, it’s not very conducive to a healthy lifestyle. That’s where discipline comes in.”

Lue talked after his return about the NBA playoffs being one of his “happy places,” the excitement and challenge outweighing any pressure or stress. Malone has a different version of getting away.

“I’ve gotten into biking,” he said. “I used to run, but my body can’t take the running anymore. So now I’m mountain biking in Colorado, even in the season if the weather cooperates. On the road, it’s walking in cities and finding ways to get out and get some time to yourself a little bit.”

Besides serving as a release valve, that high-altitude training must be doing wonders for Malone’s lung capacity, someone suggested.

“And the referees can vouch for that,” he said, with a healthy laugh.

Steve Aschburner has written about the NBA since 1980. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.