You can’t hear 24,000 fans buzzing about the novelty of pro basketball, or chuckle at Charles Barkley playfully giving the business to Karl Malone, or wonder if Dee Brown was peeking on that no-look dunk. And you certainly can’t count the seconds of hang time executed by the state symbol, a guy named Michael Jordan. Not at this location. Not anymore.

You can, however, get your grub on at the deli or take a bike ride or rent a two-bedroom apartment on this patch of land that, for a hot moment, once served as the center of the NBA universe.

Charlotte Coliseum is ancient history, abandoned by the NBA over a decade ago, then bulldozed when they paved paradise to put up a parking lot and a mixed-use development. And there’s nothing left to give the slightest hint the All-Star Game dropped by and seized the city for a weekend except your hazy memory.

This was in 1991, the only other time the annual mid-season red-carpet show was held in Charlotte. That’s almost another time and another world, certainly from an optics standpoint. As the NBA’s meal ticket, Jordan owned the entire league back then; now, he just owns one team, the Charlotte Hornets. They play at Spectrum Center in what the locals call uptown — which is really “downtown” — and once built, the arena and surrounding area instantly became the heartbeat of a city that once shut down after happy hour.

“It’s really night and day, compared to the last time we hosted the All-Star Game,” said Fred Whitfield, the president and vice chairman of the Hornets. “It really has been surreal, to be honest.”

But the All-Star Game is back in Charlotte almost three decades later because of what remains unchanged: The appetite for basketball, and of course, the power of Jordan.

When the NBA awarded teams to Miami, Orlando, Minnesota and Charlotte in the late 1980s, the expansion cities were promised the All-Star Game as a perk for their $32.5 million fee, which amazingly was considered substantial then. The NBA’s arrival awakened Charlotte, which until then lacked professional sports and therefore was minor league.

Any doubts about the NBA’s appeal disappeared almost instantly, when the Hornets lost their first home game by 40 … and received a standing ovation. That was either a sign of desperation, or appreciation, or both.

The home of the Hornets became “The Hive,” the league’s largest-capacity arena and a quirky one as well; the Coliseum sat on the southern edge of town carved out in the woods. And it was built on a budget at just $52 million, with only six luxury suites. Because it lacked cubbyholes for rich folk, the Coliseum was a dinosaur almost the day it opened and would last only 13 years.

But the place catered to pure fans and was a smash hit. The Hornets led the league in attendance in their very first season and at one point sold out 364 straight games. Muggsy Bogues was the biggest man in town, Larry Johnson and his catchy “Grandmama” commercials the biggest woman.

Whitfield was a season ticket holder from the start and an executive with Nike then, and like everyone else became sucked in by the NBA and the prestige the league brought to town. Understand that prior to the Hornets, Charlotte was a great place to raise a family and a terrible place to throw a party, and suddenly, there was activity around 7:30 p.m. when the Hornets tipped off.

“It finally put us in the big time,” Whitfield said. “It wasn’t just Charlotte; it was a big deal for the entire state to have a professional team. We hadn’t had anything since the ABA and that was many years before.”

Three years after the Hornets were born, Charlotte’s turn came up in the All-Star rotation. While Miami offered the chance to frolic on South Beach and Orlando gave everyone a reason to bring the kids along for the theme parks and Prince threw a concert when the All-Stars were in Minnesota, Charlotte offered … a reason to take a nap. The city then just wasn’t built to entertain an event on a large scale for three days and nights.

So it was up to the stars, led by the one who was the biggest and most familiar to the locals. Jordan was born and raised on Carolina clay and made the shot to win the 1982 national championship for UNC, so quite naturally he was the main attraction for All-Star weekend.

But first, he and Nike, the company he helped create into a sneaker Goliath, were upstaged by a Celtics rookie wearing revolutionary shoes from an upstart rival named Reebok.

Dee Brown was a symbol of a Boston Celtics franchise in transition in the early 1990s. The storied front line of three Hall of Famers was showing hairline cracks. Larry Bird was 34 and dealing with a creaky back, Robert Parish was 37 and Kevin McHale was 33. Fortunately, there was a youth movement — thanks to trademark clever drafting by the Celtics — led by Reggie Lewis and Brian Shaw and now Brown. He was a charismatic and athletic 6-foot-1 rookie guard with some serious spring.

Brown was a late addition to the dunk contest and not considered a threat in a field that tilted to Shawn Kemp (a lethal dunker and one of the best all time) and Hornets hometown hero Rex Chapman. And yet …

“I was confident,” Brown said. “I grew up watching the dunk contest. It was the marketing event of All-Star weekend because of Dominique (Wilkins) and Spud Webb. I knew what I could do.”

Reebok had no clue I was going to do that; they gave me no instructions and I didn’t tell them I was going to do it. I was just trying to get the crowd into it.

Dee Brown on Dunk Contest shoe stunt

Brown recalled walking into the Coliseum and taking a seat next to Kemp on the bench with the other contestants before the dunk-off.

“At that time, me and Shawn had the same haircut,” said Brown. “A few people wanted autographs and one of them looked at me and said, ‘Hey Shawn, is that your little brother?’ The guy didn’t even know who I was or why I was sitting there. That got me fired up.”

Brown quickly established himself as the new flavor, defying the laws of aerodynamics with unexpected hang time, and won over the judges with creativity and a crowd that rooted for the little guy.

Back home, a group of business executives took special interest as they watched on TV. Based in Boston, Reebok was a company anxious for traction in the competitive athletic footwear business ruled by Nike. That meant Reebok had to make a splash in the NBA because teenagers increasingly wore basketball sneakers as their everyday footwear of choice. Reebok only had Dominique Wilkins then, and he wasn’t in the dunk contest. But Brown was; Reebok signed him mainly because he was drafted by the hometown Celtics, and so there was anticipation.

And then Brown made a spontaneous decision that would turn him and the company into overnight stars.

Reebok created a shoe that, with the press of a rubber button on the tongue, would compress around the foot of the wearer, a gimmick more than anything. The “Pump” was mostly a curiosity before the dunk contest.

After TV cameras caught Brown pumping his shoe before dunking, the “Pump” flew off the shelves.

“It was something I made up the day of the contest,” Brown said. “Reebok had no clue I was going to do that; they gave me no instructions and I didn’t tell them I was going to do it. I was just trying to get the crowd into it. I didn’t know what the repercussions would be a day later or 10 years later. I had no clue. I was a kid.”

Then on his final dunk, Brown pumped his sneaker, and in mid-air, he covered his face and eyes with his forearm and … well, if social media existed then, it would’ve crashed.

When his children see replays of their father’s dunk now, they insist Brown became the first person to “dab.” Either that, or he was checking to see how well his deodorant was holding up. In any event, the improvisation forced future dunkers to get creative.

“That dunk became iconic,” he said. “I figured since I had already won the contest even before that last dunk, I wanted to do something special, something you’d talk about forever. Something like Michael Jordan and Dr. J from the free-throw line. So I just decided I’m going to close my eyes. But as I was running down toward the basket, I was thinking that nobody will know my eyes are closed, so I’ve got to put my hand over my eyes. Organically it went from my hand to my arm and then my elbow. If you look at the pictures, my eyes are closed and my arm is over my eyes, to make double sure.”

Brown added: “Back then, you couldn’t use props in the dunk contest. All these guys today jumping over cars, jumping over people, you couldn’t do that. It was a big insurance thing.”

It was a game changer for Brown. He soon had his own shoe, which was rare for NBA players then. Fans would now sprint past Bird to get Brown’s autographs on road trips. And whenever Brown dropped an ordinary dunk on a fast break, he’d get booed, so he felt pressure to perform.

Bird marveled at the transformation.

“Before,” Bird said, “everybody wanted to shoot like me. Now everybody wants to dunk like Dee.”

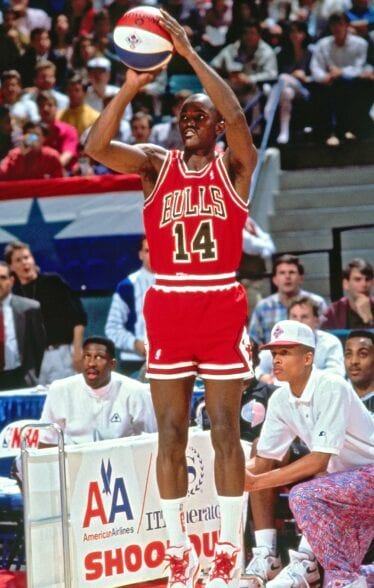

Also that day, Chicago Bulls guard Craig Hodges made 19 straight to win the 3-point contest for the second time and would win the next year as well. Nobody has erased either streaks since, although to be fair, most winners rarely compete more than twice anymore. It was ironic that Jordan was upstaged twice in a weekend made for him — first to a dunker, of all people, then to one of his Bulls teammates.

The Saturday contests were a tough act to follow, and the next day it showed in a rather flat All-Star Game, won by the East 116-114. Bird was a scratch because of injury, same for Isiah Thomas. The game had sloppy stretches, and without Thomas, the East lacked point guards, so Jordan was pressed into that duty. Oh, well: Jordan committed 10 turnovers with his 26 points and while it was an eyesore at times on TV, nobody in North Carolina held it against him.

During the game, Wilkins had a breakaway and a chance to give Reebok another weekend highlight … then he blew the dunk, everyone laughed and he heard it from teammates.

“Nique forgot to pump up,” said Jordan, the Nike guy issuing a dig.

It was that kind of night. Phoenix Suns guard Kevin Johnson had a chance to win it for the West, but his 3-pointer was waved off on basket interference by Malone.

They had to give the MVP to someone, and Barkley sheepishly claimed it with just 17 points, among the lowest scoring totals by an MV (although he did have 22 rebounds).

At least the game served to certify the comeback by future Hall of Famer Bernard King, who suffered a devastating knee injury six years earlier, and this was before modern surgical techniques. He was warmly applauded by fans and players.

Once the circus left town, the basketball aftermath in Charlotte was bittersweet. The Hornets were winners after adding Johnson (in the 1991 Draft) and Alonzo Mourning (in the 1992 Draft). Mourning was eventually dealt to Miami, Johnson injured his back and owner George Shinn became embroiled in scandal. The Coliseum sellout streak ended and fans, angered by Shinn’s behavior coupled with a losing team, came to games in a trickle.

The Hornets fled to New Orleans in 2002 and the NFL replaced basketball as the only game in town. But the NBA promised a return if Charlotte agreed on a new building, and such was the case when the new arena went up and the Hornets were reintroduced in 2004 as the Charlotte Bobcats.

By then, Charlotte was flush with new residents and a more vibrant downtown (or uptown), making it prime for the NBA once again, this time in a different part of town.

Whitfield recalled that, during the 1991 All-Star Game, he and family and friends — Jordan among them — rented a suite at the Morehead Inn, a quaint hotel tucked away in a historic neighborhood, because the city wasn’t exactly over-run with amenities and places to socialize.

“Michael would stop by in the evenings because with everything going on around him being back home, it was a comfort zone for him to be able to get away,” said Whitfield.

Now as owner of the Hornets, Jordan served as the driving force in Charlotte getting the annual weekend again, almost three decades later, because the league knows the value of keeping an association with the game’s greatest player. Whitfield works directly under Jordan and is the point man in making sure Charlotte is spruced up for the occasion.

“The NBA All-Star Game coming to Charlotte was something we couldn’t believe was reality when it happened the first time,” Whitfield said.

“But right now, with a place that’s suddenly very walkable, with great hotels and restaurants, a lot of activity and our arena right in the middle of all of it, well, this time, we can believe it. We know we belong.”

* * *

Shaun Powell has covered the NBA for more than 25 years. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.