There was a moment when Don Mattingly, a New York Yankees All-Star first baseman in the 1980s and ’90s, couldn’t discern fiction from reality.

“Honestly,” Mattingly said, “at one time I thought Babe Ruth was a cartoon character. I really did, I mean, I wasn’t born until 1961, and I grew up in Indiana.”

DeMar DeRozan grew up in Compton, Calif., not far from where the Los Angeles Lakers — and for a while, before DeRozan arrived, their Hall of Fame center Wilt Chamberlain — played in Inglewood. And yet, there was a day in San Antonio when, an impeccable source said, the five-time NBA All-Star wing thought the great Chamberlain was a figment of someone’s imagination.

Specifically, he didn’t believe that somebody once scored 100 points in a game. Too many. Witnessed by too few. No video. For that matter, DeRozan might have doubted Chamberlain’s 55 rebounds one night. Wondered if the big man really averaged 50.4 points for an entire NBA season. Or, astoundingly, if anyone could play 48.5 minutes per game across 80 games that typically last 48 (thanks, overtime).

Frankly, when you stop and think about such numbers, and assorted other Herculean feats that Chamberlain pulled off over 14 NBA seasons, it really might seem like something out of a comic book. Carried down from Mount Olympus.

“You were not surprised at anything Wilt could do,” Hall of Fame forward Bob Pettit said during the 75 Greatest celebration at 2022 All-Star Weekend. “He could do pretty much anything he wanted. One year he said, ‘I’m gonna lead the league in assists.’ And he could do that.”

Pettit was a five-time All-Star, a two-time MVP and an NBA champion by the time Chamberlain got to the NBA. He was four years older but at 6-foot-9, 205 pounds, Pettit gave up more than four inches and 70 pounds to Chamberlain, considered then and by many now as the strongest man in NBA history.

“I remember he came after me one game,” Pettit, 89, said in Cleveland. “I did something I’d rather not talk about — I brought it on myself — and I looked up and here came Wilt. He was gonna tear my head off.

“That was unusual for him. He was not a physical player. He didn’t want to get in a fight — he just wanted to be able to score his 50 points and go home, I guess. But when I saw him coming for me, I did what every red-blooded American boy did. I started backing up.”

One almost has to back up to take in the full scope of Chamberlain’s achievements, not unlike standing next to the man back in the day. Too close and you couldn’t see in full all at once.

The big man himself experienced that.

“I don’t reflect back on a lot of things I’ve done,” Chamberlain said back in February 1987 as the 25th anniversary of his storied 100-point game approached. “But when I do, I say, ‘Come on. Did I do that?’ While you’re doing them, it seems natural. Then later, you look back and say, ‘Whoa.’

Prepare to say “Whoa” a lot about Wilt.

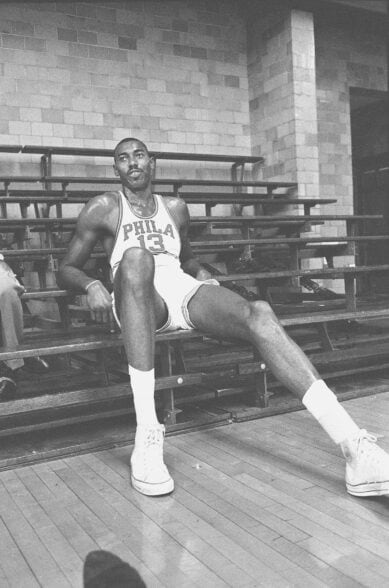

Chamberlain’s background as a one of Philadelphia’s favorite sons — right up there with Ben Franklin and Rocky Balboa — is widely known. Born on Aug. 21, 1936, raised as one of nine children by William and Olivia Chamberlain in a racially mixed, middle-class neighborhood, the young man stood a foot taller than classmates late in grade school.

At Overbrook High School, he broke records both in basketball — the varsity went 56-3 in his three seasons — and in track & field. He chose the University of Kansas for college, led the freshmen team past the upperclassmen on his first day, then scored 52 points in his official NCAA debut. Chamberlain helped the Jayhawks reach college hoops’ championship game, a triple-overtime loss by one point to North Carolina, and was named the tournament’s Most Outstanding Player.

After his junior year, Chamberlain in May 1958 opted to turn professional — though NBA rules prohibited entry into the league until the player’s college class graduated. So he spent that season playing for the Harlem Globetrotters, signing for an estimated — and exorbitant at the time — $50,000 salary.

By the time Chamberlain did enter the league as a “territorial pick” by the Philadelphia Warriors, he already was famous. He and Warriors fans savored the idea of the young behemoth freed from the zone defenses that bothered him in college. Man-to-man? Coping with Chamberlain in the NBA was going to be become man-to-mountain.

In time, the league would change rules to help teams try to thwart him: Revising goaltending rules, widening the lane again (first changed for George Mikan) and tightening free-throw requirements to stop Wilt from taking a running start, launching from the foul line and dunking his free throws.

The excitement over Chamberlain’s NBA arrival reportedly even had owners of opposing teams excited over the profits from sold-out arenas. Maybe not so much, though, the players who’d have to guard him.

In his first NBA game, a victory over the Knicks in New York, Chamberlain scored 43 points – two more than Michael Jordan and LeBron James combined in their debuts.

Over his first 15, he averaged 36.9 points and 30.5 rebounds. And Philadelphia went 11-4, including 2-1 against the defending champion Boston Celtics. Chamberlain averaged 41.3 and 32 to Bill Russell’s 18.5 and 24 in those initial head-to-head matchups between automatic rivals.

Come March, he had put up one of the most incredible rookie seasons ever, not just in the NBA to this day but across major sports: 37.6 points per game, 27.0 rebounds and 46.4 minutes. He not only was named Rookie of the Year but MVP of the 1960 All-Star Game (played in his hometown) and NBA MVP overall.

In 75 NBA seasons, only he and Baltimore’s Wes Unseld in 1969 ever snagged both the ROY and season MVP. Before Chamberlain was done, his list of accomplishments and records would stretch as long as his inseam.

One hundred.

It was a newspaper typographer’s nightmare at the time, having to cram three digits into a box score template where only two ever had been needed. But on March 2, 1962, Chamberlain turned it into reality by scoring 100 points in a single NBA game, a record that has endured across 60 years and become iconic in pro sports and the culture.

Less than three months earlier, the Warriors’ big man had set the NBA record of 78 in a triple-overtime game against the Lakers. There was no hint that anything special was going to happen in Philadelphia’s 76th of 80 games that season, other than the fact Chamberlain also had put up nights of 73 and a dozen more scoring at least 60 points.

The contest was staged as a one-off in Hershey, Pa., site of the Warriors’ preseason training camp but better known as the chocolate capital of the USA. The Hershey Sports Arena was small but that wasn’t an issue, with only 4,124 fans in attendance that night.

Over time, of course, and based on Chamberlain’s historic performance, the crowd size has ballooned.

“I don’t want to add to the mystique,” he told me in that February 1987 phone interview, “but just in my life, people that have come up to me, I’d say 20,000 to 25,000 say they were at the game. And usually they say they saw me do it at ‘da Gahden.’ Y’know what I’m saying?”

Chamberlain sighed. “Now I’m sarcastic about some things. I tell people what I think,” he said. “But that’s the only time I let them get away with a lie.”

Chamberlain’s recollections were that he had spent the night before the game with a lady friend. He nearly missed an 8 a.m. train to Hershey. When he arrived, he met up with some other friends, went to a game arcade and powered through without much sleep right to tipoff. It wasn’t the first time.

He scored 41 points in the first half, more than anyone else on the Philadelphia or New York rosters managed all night. When he got to his record 78, Warriors public address announcer Dave Zinkoff started giving his running point total with each score. Soon, the fat round number of 100 began to look like a possibility.

The Knicks didn’t like the prospect of being the victims of such a feat, so late in the game they began fouling Chamberlain’s teammates to send them — not him –to the free-throw line. The Warriors wanted to witness 100, though, so they quickly fouled New York players at the other end to get the ball back.

Wilt finished with 36 field goals on 63 attempts — embarrassing himself with the number of shots — and an unbelievable (for him) 28 free throws on 32 attempts. He had 25 rebounds in the 169-147 victory, to that point the highest scoring game in NBA history. And he played all 48 minutes, although records don’t show how the final 46 seconds were canceled when fans rushed the floor after Chamberlain’s last bucket.

Someone shoved into his hands a sheet of typing paper with a hastily scrawled “100” on it for what became one of sports’ most famous photographs. And in what might be an apocryphal tale, a wire service report somewhere supposedly began with the old-style lead, “Wilt Chamberlain and Al Attles combined for 117 points on Friday as the Philadelphia Warriors beat …”

Want some perspective on the achievement? Kobe Bryant scored 81 in a game in January 2006 (benefiting from seven 3-pointers). David Thompson got 73 in 1978. Wilt himself scored 70 or more six times out of the 11 it has been done.

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about his 100-point performance is that no two teammates have combined to score that many or more in any other game in league annals.

Some have diagnosed Chamberlain with what they call a “Goliath complex.” Certainly he used the term in the 1960s when he said of himself, “Nobody roots for Goliath.”

Some have diagnosed Chamberlain with what they call a “Goliath complex.” Certainly he used the term in the 1960s when he said of himself, “Nobody roots for Goliath.”

No one seemed more determined than him to tell the world how proficient he was at, well, almost everything. Volleyball, high jump and broad jump events in track, backgammon, chess, cooking, investing and so on. He entertained notions of boxing, even challenging Muhammad Ali to a mythical fight hyped by ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.”

Then there was his mathematically dubious boast in the early ‘90s about bedroom conquests.

But Chamberlain needn’t have bothered. His on-court basketball deeds were more than enough to etch his legend into record books and memories. Many of his marks still stand, and notable achievements for mere mortal players — scoring 50 points in a game, for instance — Wilt did seven games in a row, 118 times in his career and four more in the playoffs.

He dwarfed others’ personal bests as if he were standing next to children.

Beyond his scoring (31,419 points in 1,045 games, a 30.1 average) and rebounding (23,924, 22.9), it’s worth noting that the NBA did not track blocked shots or steals as statistical categories until the season (1973-74) after he retired. Chamberlain would have had a bevy more triple-doubles than his official 78, maybe even quadruple- or quintuple-doubles.

Still, his “A” game was his scoring, and his athletic ability was matched by an arsenal of finesse skills that produced not just dunks, but fadeaways, finger rolls and — as a template decades later for Tim Duncan — uncanny turnaround bank shots.

Boil it all down and there are two great individual rivalries in team sports, and they both happen to have played out in the NBA.

- Larry Bird vs. Magic Johnson

- Wilt Chamberlain vs. Bill Russell

The former arrived ready-made from the 1979 NCAA men’s basketball championship game. They landed with the league’s two most famous franchises and, over the next 8-10 years, already were considered to have saved the league from a slow, undeniable popularity swoon in the 1970s.

The latter pitted a pair of fierce competitors who were studies in contrast, too. One represented offensive and individual dominance while the other was all about defense and team results.

The Celtics’ center, at 6-foot-9 and 215, couldn’t match the other guy’s sheer physical dominance. Yet his collection of 11 championship rings in 13 seasons bedeviled Chamberlain, whose team broke through against that Boston dynasty just once, in 1967.

Their battles were highlights of the NBA schedule. Unlike the Bird-Magic clashes, limited by conference to just two regular-season matchups each year, Chamberlain and Russell routinely faced each other 10 times or more before any playoff showdowns.

In the 10 seasons they overlapped – 1959-60 through 1968-69 – they played against each other 142 times, including the postseason. Chamberlain averaged 28.7 points and 28.7 rebounds to Russell’s 14.5 and 23.7. Russell spent his entire career with the Celtics while Chamberlain played for the Warriors, the Sixers and the Lakers.

Russell’s teams won 85 times, Chamberlain’s 57 head-to-head. Boston won nine championships, Philadelphia one during those 10 years. Each man was named MVP four times in the decade, with only Oscar Robertson (1964) and Unseld (1969) breaking through.

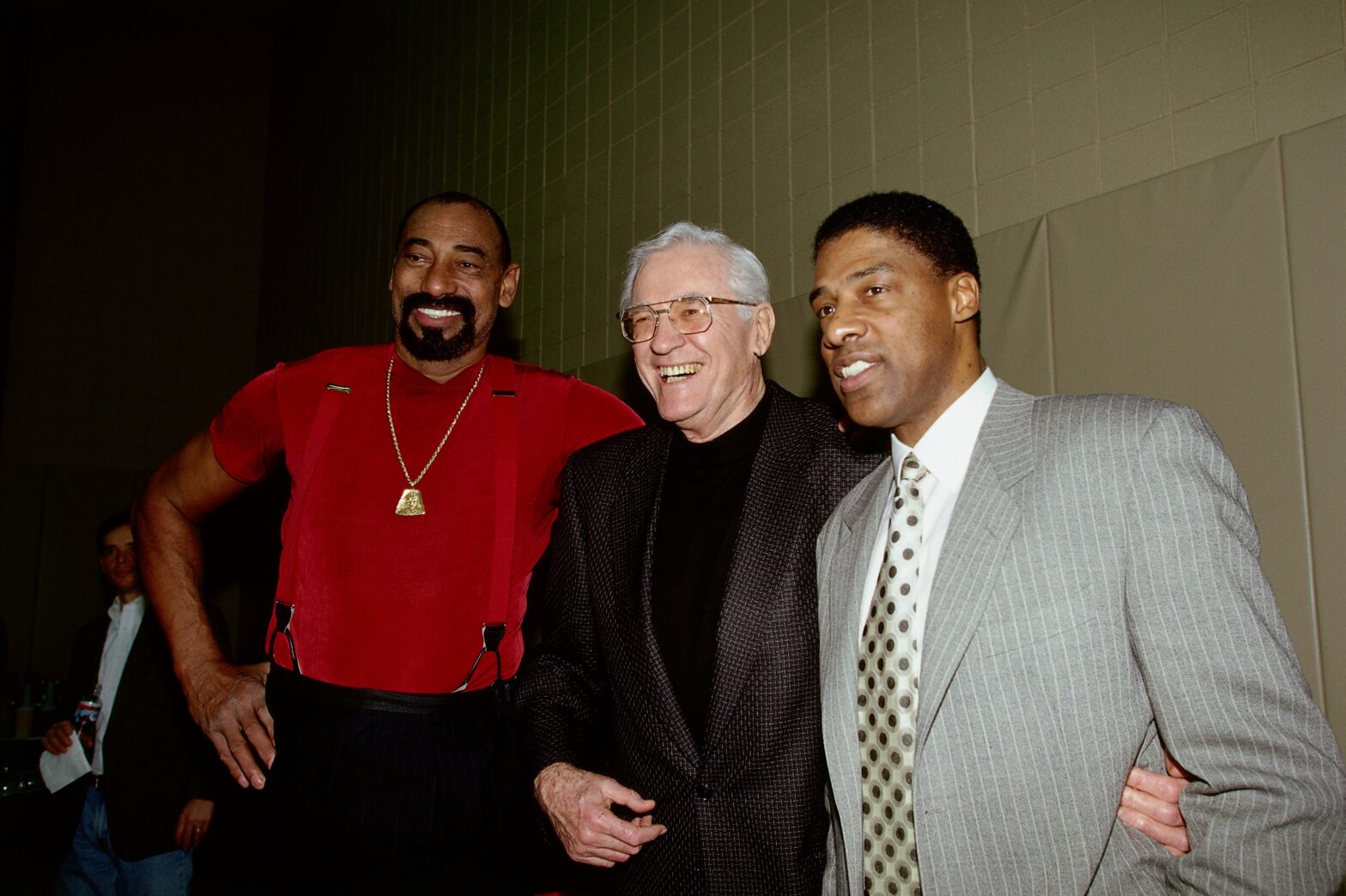

What most people didn’t realize was that the two were great friends. As proud, high-profile, unusually tall black men playing the same position in the same sport in 1950s and ’60s America, they had more in common than not.

The two regularly dined together the night before games, often at Russell’s house when meeting up in Boston. And for all their ferocity on the floor, they were (save for one extended falling-out) forever grateful and generous, commending each other for bringing out their maximum effort and abilities.

When Chamberlain died at age 63 in 1999, Russell issued a statement that we all should be so lucky to get from someone at the end.

“I feel unspeakably injured,” he wrote. “I’ve lost a dear and exceptional friend and an important part of my life. Our relationship was intensely personal.

“Many have called our competition the greatest rivalry in the history of sports. We didn’t have a rivalry; we had a genuinely fierce competition that was based on friendship and respect. We just loved playing against each other. The fierceness of the competition bonded us as friends for eternity.

“Wilt was the greatest offensive player I have ever seen … Because his talents and skills were so super-human, his play forced me to play at my highest level. If I didn’t, I’d risk embarrassment and our team would likely lose.”

Both Chamberlain and Jerry West suffered through the 1960s having the bad luck of being born at the wrong time, on a collision course with one of the most machine-like dynasties in sports. The Celtics, as built and coached by Red Auerbach (later Russell for two years as player-coach) and led by their great center and another nine Hall of Famers, treated the rest of the league like little brothers.

Both “Mr. Clutch” and “The Big Dipper,” the nicknames by which they became known, agonized over their inability to win a title. West, the sharpshooting guard from West Virginia, turned his angst inward, beating himself up psychologically for his failure to break through. Chamberlain sometimes reminded listeners that it was a team sport, alluded to the quality of certain Celtics besides Russell and even went philosophical about the value of sports in the grand scheme, anyway.

That was apart, however. Then West and Chamberlain teamed up, the big fella pushing for and getting a trade to the Lakers in 1968.

Together, with fading legend Elgin Baylor, they would fall to Boston once more in the 1969 Finals. But that begin a string of four Finals appearances in five seasons together. And in 1971-72, foreshadowed by 33 consecutive victories that remains the longest such streak in league history, the Lakers tore through Chicago, Milwaukee and New York with a 12-3 postseason mark to win Chamberlain’s second and West’s only NBA championship.

And before they banned together, Chamberlain and West also went head-to-head. And this feature from deep in the vault captures a random regular-season meeting, with Chamberlain’s Sixers in Los Angeles to face West and the home team Lakers.

We hear it often in sports, the questions about eras and specialness of players and whether this guy or that guy would be able to play then or now. Analytical tools get pulled out, recency bias often revs up and folks who never saw all parties play make pronouncements about who could do what, and when. Most of it is sheer speculation, barroom banter.

Chamberlain did almost get the chance to find out for a while. In the 1980s, he was approached by the Cavaliers, the Nets and another team or two about considering a comeback as a backup center. His ego loved it, but he declined.

Look, times change, rules change, sports change. Chamberlain played during an era when talented big men ruled the league like dinosaurs walking the Earth, facing peers such as Russell, Unseld, Walt Bellamy, Nate Thurmond, Willis Reed, Zelmo Beaty, Wayne Embry and eventually Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bob Lanier. Today’s centers — with a few exceptions such as Joel Embiid and Nikola Jokic — don’t compare.

Then again, Chamberlain never felt the isolation of seeing his man, a “stretch five,” drift out 24 feet from the basket to hoist 3-pointers. But if you’re going by skill set and mobility, it’s easy to imagine him being athletic enough to adapt and even stretch his shooting range to suit.

And if you’re going by sheer size, it’s worth a look at Chamberlain’s stature relative to more recent Hall of Fame centers such as Shaquille O’Neal, Patrick Ewing, David Robinson and Hakeem Olajuwon. At age 50 and beyond.

wi

It’s a tribute to Chamberlain’s dominance that he can get used as an adjective for some of sports’ whoppers. Wayne Gretzky’s NHL-record 215 points in 1985-86? Nolan Ryan pitching seven no-hitters? Secretariat completing the 1973 Triple Crown by 31 lengths at the Belmont Stakes?

All “Wiltian.”

Chamberlain’s feats of strength and excess were renown. He allegedly would drink a quart of milk and eat half a pie at halftime some nights. Opponents were grateful that he almost never played “angry,” lest he break someone’s arm dunking over their feeble attempts to block.

“I spent 12 years in his armpits, and I always carried that 100-point game on my shoulders,” said Darrall Imhoff, one-time All-Star center who had the misfortune of defending Chamberlain on that momentous night in Hershey and again two nights later in New York when he scored 58.

“He was an amazing, strong man,” Imhoff said. “I always said the greatest record he ever held wasn’t 100 points, but his 55 rebounds against Bill Russell. Those two players changed the whole game of basketball. The game just took an entire step up to the next level.”

Don’t forget Chamberlain’s ability to find his teammates. When he got tired of folks dismissing him only as a scoring giant, and challenged by his coach Alex Hannum at the time in Philadelphia, he decided to focus on assists. He bumped his average from 3.8 in 1964-65 to 5.2, 7.8 and 8.2 the next three years. And in 1968 set the season record for total assists by a center of 702.

Like Michael Jordan laying down a standard for wing players that Kobe Bryant and LeBron James could identify and chase, Chamberlain really established more records than he broke.

And like Oscar Robertson once said about triple-doubles, that if he’d known they would become such a big deal, it seems clear Chamberlain would have put his marks farther out there than they already were.