Passing of Laker's Legendary Announcer: Chick Hearn

Passing of Laker's Legendary Announcer: Chick Hearn

Remembering A Lakers' Legend

2007-08 by Mark Heisler

This year, the Los Angeles Lakers are pleased to have former Lakers beat-writer and current Los Angeles Times columnist Mark Heisler share some of his stories about the broadcasting icon. Heisler, who has covered the NBA for 24 years with the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Philadelphia Bulletin and the Los Angeles Times while also writing four basketball books, received the Basketball Hall of Fame's Curt Gowdy Award in 2006 for his contributions to the game.

Everything about Chick Hearn was larger than life, including his reputation which was already imposing when I first heard of him in 1969. Chick was in his ninth season as the voice of the Lakers and already their living embodiment. I was in my first season as an NBA writer in Philadelphia, which was hosting the All-Star Game. The hotel which housed everyone had run out of rooms and Chick, arriving at the front desk, was asked if he would room with someone else there for the event.

"Hearn doesn't share a room," Chick is supposed to have announced and stomped across the street to another hotel.

In an era of larger-than-life announcers like Marv Albert in New York and Johnny Most in Boston, there was still just one Chick whose personality was as commanding as his booming voice and his considerable reputation.

You could argue that in show-biz Los Angeles where Vin Scully was already a hit, Chick's arrival on the scene for Game 5 of the Lakers' first playoff series against the St. Louis Hawks in 1961 was almost as important as those of Jerry West and Elgin Baylor.

A scene in the 1973 movie, "Blume in Love" suggests how fast Chick came to be identified with the Lakers and Southern California. Looking for local color, director Paul Mazursky had George Segal driving his Porsche into the Hollywood Hills to visit his estranged wife, with Chick's call of a game blaring on his car radio.

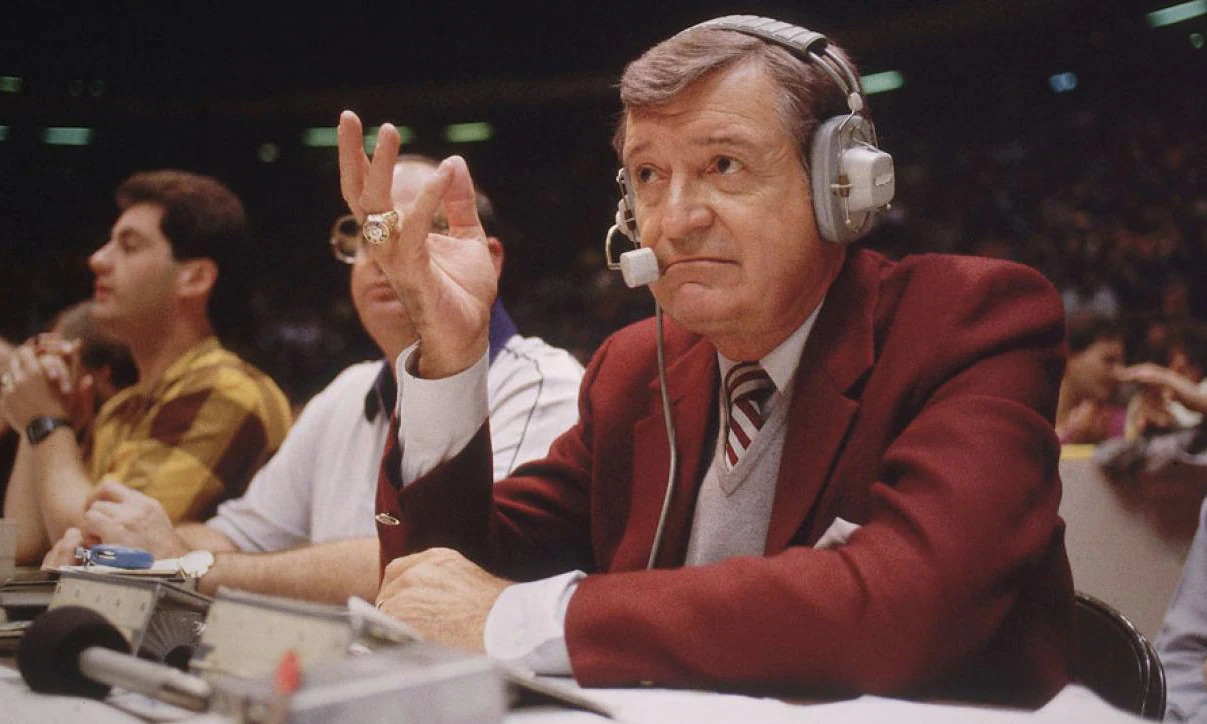

Chick Hearn smiles as he introduces the Los Angeles Lakers on the podium at the Laker victory rally honoring their third consecutive NBA Championship at Staples Center. Chick wasn't just commanding, he was like a force of nature. No one actually called him "the Iron Mike"-Chick was always Chick--but iron, he was.

He was tireless, doing hours of homework, even calling imaginary action to warm up before games. He took all the outside work he could get, hosting "Bowling for Dollars" and doing college football games for ABC. His 3,338-game streak would have been four seasons longer if bad weather hadn't cancelled his flight home from Arkansas in 1965.

He did UNLV basketball as well as the Lakers in the '80s when he was in his 60s. (Chick's age was always a closely guarded secret but my boss at the Times, sports editor Bill Dwyre, was related to him by marriage and knew what it was.)

For years, Chick was as much part of the brain trust as the act. Serving as assistant GM to Fred Schaus, it was Chick who suggested bringing in journeyman Pat Riley from Portland.

In 1977 with Lynn Shackleford leaving for Channel 9, Chick helped Riley put together the audition tape that convinced Jack Kent Cooke to hire him.

A bad knee had ended Riley's journeyman career, leaving him on the beach at Santa Monica, literally, seeing how long his beard would grow.

"I asked him if he wanted to make a couple tapes, present them to Jack Kent Cooke," Chick said years later.

"He was pretty nasal at the time. I thought, 'Oh, gee' to myself, 'Cooke will never accept this guy.'

"Anyway, we would sit and watch games with the sound turned off. I would do my thing and he would do his color.

"After he did it many, many times-Cooke didn't even know I was interviewing him-I said, 'Here's a tape I think we can take to Cooke.'

"So I took it in. I thought we'd get thrown out of his office. And Cooke says, 'My Gawd, Chick! This boy is wonderful! Just what we need!'"

The Lakers color commentator was then also the traveling secretary so when the Lakers boarded flights, Riley was the one giving everyone their boarding passes.

"Players used to throw them back at me," said Riley. "'I don't want 1A. I want 1D. I don't want to sit next to that guy."

In Riley's third season, the new coach, Jack McKinney, was hospitalized for months after falling off his bicycle. His young assistant, former LaSalle Coach Paul Westhead, brand new to the NBA, was forced to take over, working alone.

Westhead asked if Riley could come down and help him out. Everyone in the organization, starting with Jerry Buss, wanted someone with coaching experience. "Riles came to me and said, 'I've been asked to do this, what do you think?'" said Chick.

"I said, 'Let me think.'

"I thought about it. I thought about his dad. I thought about Adolph Rupp [whom Riley played for at Kentucky.] I thought about his contribution to the NBA. I thought about his work habits."

"I finally said the next day, 'I think you can do it.'

"And he said, 'What if I don't make it?'

"I said, 'I'll give you a written contract. You can come back in the booth any time you want.'"

The rest was history, or as the Lakers like to think of it, Showtime, when they won five titles in the '80s, the last four under Riley.

"Maybe he saw something in me I didn't see," said Riley. "All I know is that if Chick hadn't advised me to take the job, I wouldn't have done it."

Chick was always great to me, which was a relief. I was in awe of him from the day I saw him board the Lakers bus talking a mile a minute, cutting up anyone who stuck his head up. Faced with that machine-gun delivery, few fired back.

His early color commentators, like Al Michaels who lasted one game, had the same problem. The long-running joke was all they could say was, "Right you are, Chick."

I remember one of them, Keith Erickson, giving a toast at the wedding of then-Times columnist Scott Ostler. Said Keith, arriving at the microphone, "Right you are, Chick."

Chick had the cachet to call 'em as he saw 'em. He didn't underplay their exploits but his idea of candor was so brutal, when they lost, it sounded as if they'd never win again.

Happily, they were an elite team for his entire stay, with nine titles, 22 Finals appearances and 40 playoff appearances in his 44 seasons.

That was the way it was supposed to be. Hearn didn't rebuild, either.