And, just like that, “they’re not gonna rook us” enters the NBA’s all-time lexicon.

Memphis’ first-year coach, David Fizdale, surely wasn’t looking to say something memorable when he sat down following the Grizzlies’ Game 2 loss to the San Antonio Spurs last week. He was an angry, frustrated coach, whose team had battled all game long, gotten close, but come up short in the end. And Fizdale blamed the game’s referees for much of that shortness: his team had shot 15 free throws total, while the Spurs’ Kawhi Leonard got to the foul line 19 times by himself.

Worse, to Fizdale, the Grizzlies weren’t rewarded for their aggressive inside play.

“First half we shot 19 shots in the paint and we had six free throws,” Fizdale said. “They shot 11 times in the paint and had 23 free throws. Not a numbers guy, but that doesn’t seem to add up. We don’t get the respect that these guys deserve, because Mike Conley doesn’t go crazy, he has class, and he just plays the game, but I’m not gonna let them treat us that way.

“I know Pop’s got pedigree,” Fizdale continued, and Game 2 was, to be precise, Popovich’s 254th postseason game — and Fizdale’s second. “And I’m a young rookie. But they’re not gonna rook us. That’s unacceptable. That’s unprofessional. My guys dug in that game and earned the right to be in that game. And they did not even give us a chance. Take that for data!”

And, just like that, he was gone.

Fizdale was soon relieved of $30,000 for his statements, but his point was made. And the Grizzlies and their inspired crowd came roaring back to tie the series at two after an epic overtime win Saturday.

No matter how the series turns out, though, Fizdale is immortal, his anger distilled into a catchphrase that will live on among the all-time remembered phrases in NBA history.

To make this list, a phrase or utterance must be unique, it must be to the point, it must be understandable and it must have resonance that extends well beyond the specific circumstances under which it was said. A brief but by no means exhaustive list of such immortal lines would include:

“The ship be sinking.” (Micheal Ray Richardson, 1982, during his New York Knicks’ late-season collapse.)

“Never underestimate the heart of a champion!” (Rudy Tomjanovich, in 1995, after the Rockets won their second straight NBA title.)

“I’m Back.” (Michael Jordan fax announcing his return to the NBA, 1995.)

“Anything is possible!” (KG, post-Finals championship, 2008).

And, of course … ”we’re talking about … practice”.

But Rick Pitino was in no laughing mood after his Boston Celtics lost a buzzer beater to the Toronto Raptors in 2000, when asked how he planned to keep his players’ spirits up.

“Larry Bird is not walking through that door, fans,” he said. “Kevin McHale is not walking through that door. And Robert Parish is not walking through that door. And if you expect them to walk through that door, they’re gonna be gray and old. What we are is young, exciting, hard-working, and going to improve.”

(Postcript: they didn’t — at least not enough for Pitino to keep his job.)

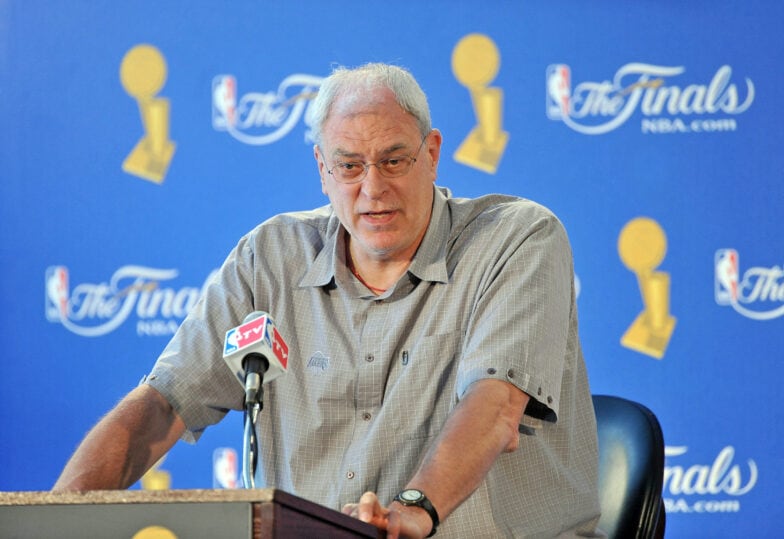

And there was Phil Jackson, in his final presser as coach of the Los Angeles Lakers in 2011, after being swept by Dallas in the Western Conference semifinals. The Mavericks’ coach, Rick Carlisle, had opined that Jackson — who’d insisted he’d never coach again — would return to the sidelines “after meditating and smoking peyote in Montana.” The great L.A. sports anchor Jim Hill then asked Jackson about it.

“Well, first of all, you don’t smoke peyote, that’s one thing,” Jackson said, to guffaws from the Fourth Estate.

Coaches whose words live on are even more special.

Almost always being older than their players, they are supposed to be the ones who bring a calm, reasoned approach to postgame remarks, having gone through years and years of such news conferences, knowing how to work the media and being able to think on their feet. And they almost always do.

But when they don’t … it’s magical!

“Your adrenaline is out of control. Either bad or good. Even after wins. You’re tired and your emotions are raw. It has happened in the past and it will happen again, because that’s just human nature.”

Houston Rockets coach Mike D’Antoni

“You do it to show your team, hey, we’re fighting; we’re not dead,” Rockets coach Mike D’Antoni said Friday. “And then rally the troops back home. That’s the good side of it. The bad side of it is, you’ve got to pay a lot of money (after). And the NBA’s right. There’s always two flips to it. But, obviously, something worked. Was it worth $30,000? Everybody’s got to make that personal choice.”

Occasionally the moments are funny. Hall of Fame Coach Dick Motta was, in 1978, coaching the Washington Bullets, then up 3-1 over the heavily favored Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Conference finals. A reporter, jumping the gun, was said to have asked Motta how it felt to be in The Finals? Motta, noting his team had not yet reached The Finals, uttered the line, “the opera ain’t over until the fat lady sings.” He’d heard that line a few weeks earlier, uttered by San Antonio sportswriter and TV anchor Dan Cook during the Spurs’ semifinal series with the Bullets, and repurposed it. (Motta recalled the circumstances in a Q&A some years ago.)

Jackson was the best ever at using playoff news conferences to drive home points of emphasis to the referees — the ones working the next game — by crushing the refs who’d worked the last game. While with the Chicago Bulls, he sparred with Pat Riley, who was then coaching the New York Knicks. No wallflower himself, Riley said during a Chicago-New York playoff series that Michael Jordan got all the calls; Jackson responded by saying that Patrick Ewing traveled every time he touched the ball.

After Reggie Miller blatantly pushed off of Jordan in Game 4 of the Eastern Conference finals in 1998, clearing himself to hit a game-winning 3-pointer, Jackson said the final moments were “Munich, ‘72, revisited,” referring to the controversial (and, many in the United States still believe, illegal) last-second victory by the Soviet Union over the U.S. men’s team in the gold medal game.

In 2002, when his Lakers met the Sacramento Kings in the Western Conference finals, Jackson went all in. He engaged in seemingly daily rants about the Kings’ big men flopping against Shaquille O’Neal. After Game 2 of the series, when Shaq got three charging fouls against him, Jackson basically questioned the manhood of the refs working the game, which was in Sacramento.

“You’ve got to give some latitude to referees being in an environment like that,” Jackson said. “It’s always a question, as to what type of a group you send to a situation like Sacramento, where it’s a bandbox, where there are intense pressures. I’m sure we’re going to see a stronger crew in L.A.”

Jackson was only following the time-honored tradition of the man many believed was, until Jackson won 11 titles as a coach, the greatest ever to work the sidelines — Hall of Fame Coach Red Auerbach, whose Boston Celtics won 11 titles in 13 seasons. Auerbach received multiple fines over his years for his caustic remarks to and about officials to the media, and was suspended for three games in 1961 after being ejected in consecutive games.

The intent in all of this, of course — from Auerbach to Jackson to Fizdale — is to plant a seed in the minds of the next group of referees, to have them think twice before blowing the whistle, to put doubt and/or suggestions in their heads. But if it is understandable from the coaches’ point of view, it nonetheless feeds a narrative that all too many fans buy into easily — that the officials are incompetent and/or cheating. The cheating, of course, only is against their favored team, never for it.

There is an element of kabuki theatre in what the coaches say, too, but that nuance is almost always lost on fans. And the Jacksonian rants took their toll.

Even if fans didn’t think the refs were cheating, they’d find secret co-conspirators in the form of the broadcast networks, whose unyielding desires to have longer playoff series clearly were passed down from the league to its officials.

But with rare exceptions, Commissioner David Stern, who ruled with authority in all matters involving his league, often had a lighter touch toward coaches who fulminated postgame. The league didn’t want to overreact, knowing the pressure that all coaches face in the playoffs, even as it knew the corrosive effect of the constant carping.

As the game continued to focus on the talents of the players, and their reputations continued to grow in the 1980s and ‘90s, the league didn’t want to draw attention away from the floor by issuing large fines and suspensions on coaches. Stern’s successor, Adam Silver, has addressed the issue more subtly, increasing transparency in how the league monitors its refs’ performance through tools like the Last Two Minute report, and through making its Replay Center referee and supervisor feeds available in every arena.

And, sometimes, we have to allow that coaches just lose it, and are genuinely angry.

“In college,” Oklahoma City’s Billy Donovan said Thursday. “It happened in college. Like Fiz, I had to pay for it, too.”

Playoff games are also different because the two teams know so much about one another, leading to a lot more contact as players anticipate what their opponents are going to do, and try to beat them to their favorite spots on the floor.

“All the coaches do is sit around and watch tape,” Donovan said. “The players know everybody’s plays and what they’re running. They know what’s coming. And you’re trying to get every possible little advantage you can. And sometimes for the officials, it’s really, really hard to officiate the games, and they try to do their best job.”

There’s a reason the time between the end of a game and when the media can speak with coaches and players is specifically called the “cooling off” period. Every professional sport requires a physical and mental sacrifice that almost no human is capable of giving. Having achieved that, these highly competitive people are then put in conflict against one another, on a public stage, for several hours. Emotions are scraped raw — especially in the playoffs, the culmination of months, something years, of work and dedication. And then, just a few minutes after being at that apogee, we ask the participants to summarize their emotions and experiences. Most do it very well. Fizdale does it very well.

Most of the time.

“Your adrenaline is out of control,” D’Antoni said. “Either bad or good. Even after wins. You’re tired and your emotions are raw. It has happened in the past and it will happen again, because that’s just human nature.”

And, it plays well back home.

Fizdale is already a hero in Memphis (literally; look at this headline). He got a standing ovation at FedEx Forum when he came out for Game 3 Thursday. T-shirts, of course, quickly followed. And the Grizzlies shot 24 free throws in Saturday’s win to San Antonio’s 17.

Meanwhile, the Bulls’ Fred Hoiberg thinks Isaiah Thomas carries the ball every time down the floor.

Take that for data.

Longtime NBA reporter, columnist and Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Famer David Aldridge is an analyst for TNT. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.